The ABCs of veterinary dentistry: T is for treatment

While therapy for oral health problems can be challenging, its also very important for patient wellbeing. A good place to start? The four Rs: recheck, remove, repair or refer.

Halitosis, malpositioned teeth, oral tumors, fractured teeth, oral ulcers, swellings under the eyes-what to do? For many veterinarians, treatment is the most challenging aspect of dentistry due to the needs for client consent, specialized equipment, time and training.

Seeing our patients' lives improve and sharing the bliss of their owners' appreciation contributes to the joy of veterinary dentistry.

It's often simpler to overlook dental pathology-but it's not right for the patient, client or practice. We became veterinarians to relieve suffering, and providing dental therapy followed by prevention ensures the best for our patients. In addition, seeing our patients' lives improve and sharing the bliss of their owners' appreciation contributes to the joy of veterinary dentistry.

A straightforward approach to dental treatment is well within the scope of general veterinary practice. Most dental therapy strategies fall into one of four buckets, or the four Rs: Recheck, remove, repair or refer. Let's look at each of these in turn.

Recheck the patient

It can be hard to do nothing when you discover an abnormality, but sometimes it's in the patient's best interest. The decision to follow up and recheck an oral health problem rather than actively treat it should be based on whether the abnormality is nonfunctional (actively treat) versus functional (recheck), progressive (actively treat) versus nonprogressive (recheck), and painful (actively treat) versus nonpainful (recheck).

Remove teeth or oral masses

Fortunately, domesticated dogs and cats do not need teeth to survive. What they need is a healthy, pain-free mouth. In addition to dental scaling and polishing, extractions are the primary treatments we provide to dental patients. Often by the time we see dogs and cats with advanced dental disease, the teeth should not be saved; removing them usually resolves the problem effectively.

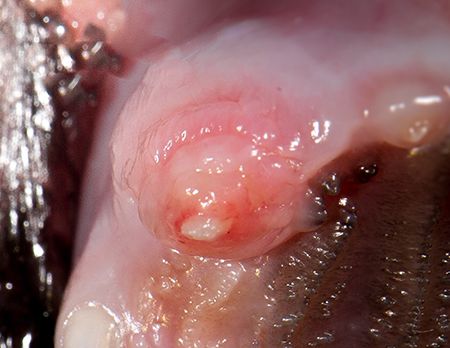

Oral masses, including gingival enlargement, can also be treated through complete or partial removal. Benign masses generally will not recur after at least 1-cm clean surgical margins in all directions have been achieved. With malignant masses, 2-cm margins are recommended.

Repair the lesion

Some oral lesions can be repaired versus addressed via tooth removal. Examples include sealants used to treat enamel hypoplasia, light-cured acrylic resin to repair enamel defects, and CO2 laser treatment of oral ulcers.

Refer to a veterinary dentist

Patients requiring advanced dental procedures can be referred to a dental specialist (visit the American Veterinary Dental College website at avdc.org to find one). The veterinarians listed are comfortable handling complex dental procedures and anesthesia concerns.

Before you make the referral, it's best to call a dental specialist personally to explain what the patient is being referred for, whether preanesthetic laboratory results and radiographs will be accompanying the patient, if it's OK for the specialist to evaluate (and treat) the entire oral cavity in addition to the specific referred issue, and whether you prefer to handle the follow-up rechecks or wish the specialist to do them both in the short and long term. This phone call also makes the client feel more comfortable about the process. Be specific. For example:

- You want the specialist to treat the immediate problem and not address any other dental issues. You want to see the patient back as soon as possible. Or …

- You want the specialist to treat all dental issues found and follow up until they are completely resolved. You expect to see your patient back to continue all future routine dental care. Or …

- You want the specialist to take care of all current and future dental issues. You do not have the necessary equipment or are not comfortable performing dental procedures.

The four Rs in the trenches of daily practice

Here's how the four Rs might play out with some of the common oral health scenarios veterinarians face in general practice.

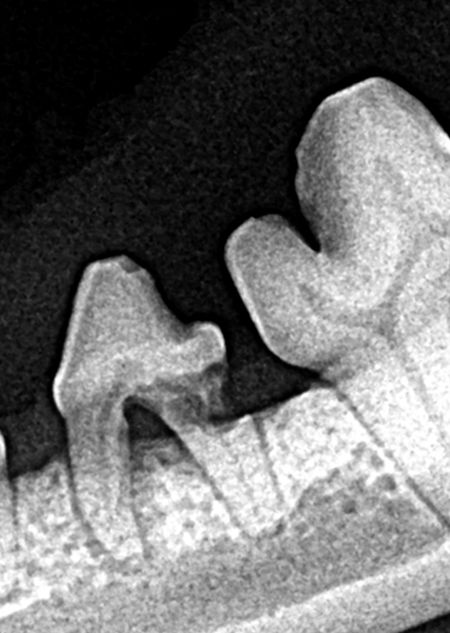

Periodontal diseases. Periodontal diseases are the most common maladies affecting dogs and cats. They are more common than gastrointestinal, dermatologic and orthopedic diseases combined. The treatment decision can be funneled down to one concept-if a tooth does not have at least 50% solid bone and/or gingival support as evidenced by mobility, probing, intraoral radiographs or some combination of the above, it's best to remove it (see Figures 1A to 1C). (All photos courtesy of Dr. Jan Bellows.)

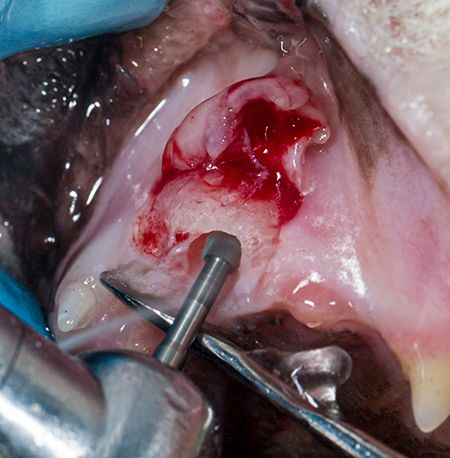

Stage 4 advanced periodontal disease affecting the mandibular canines in a dog. Extractions are indicated

Figure 1B

Radiography confirms advanced periodontal disease.

Figure 1C

The dog's postoperative appearance.

Teeth with greater than 50% support and periodontal pockets can be repaired with root planing plus or minus locally applied antimicrobials (see Figures 2A and 2B) and stringent home care. If gingival recession is the cause of the support loss, locally applied antimicrobials are not indicated.

Figure 2A

Stage 2 early periodontal disease with bleeding on probing.

Figure 2B

Treatment: Local antimicrobial ad

These treatments should be followed with recommendations for daily preventive care such as toothbrushing, wiping, and use of products accepted by the Veterinary Oral Health Council (VOHC). If the client cannot commit to daily home care, removal of teeth with less than 50% support loss may be necessary.

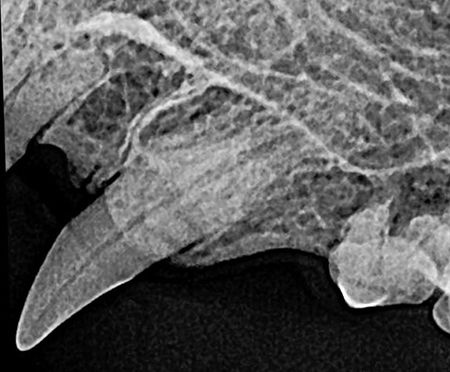

Tooth resorption. External tooth resorption is a common finding in our patients thanks to detection on intraoral radiographs performed during professional oral assessment, treatment and prevention (oral ATP) visits. When the resorption visibly or radiographically extends into the oral cavity, the treatment decision is easy: remove (see Figures 3A to 3C).

Figure 3A

Marked root resorption affecting a cat's left maxillary canine tooth; extraction is indicated.

Figure 3B

Root resorption of a dog's left mandibular fourth premolar extending to the oral cavity; extraction is indicated.

Figure 3C

Right and left maxillary canine root resorptions extending to the oral cavity; extractions are indicated.

Tooth resorption isolated below the gingiva is not considered to be painful and can be followed through rechecks (see Figure 4) or proactively extracted.

Figure 4

Root resorption of a cat's right maxillary canine radiographically confined below the gingiva; follow-up is indicated

Internal root resorptions are treated either with extraction or root canal therapy. Those rare cases with root replacement resorption (type 2) as evidenced by decreased root opacity can be treated with crown reduction followed by gingival closure (see Figures 5A to 5E).

Figure 5A

Figure 5B

Figures 5A and 5B are root replacement resorption (type 2) confirmed radiographically.

Figure 5C

Figure 5D

Figures 5C and 5D. Type 2 resorption treated by crown reduction (5C) and gingival closure (5D).

Figure 5E

Postoperative radiograph confirming proper crown reduction.

Orthodontic diseases. Occlusion is the contact between the masticating surfaces of the maxillary and mandibular teeth. Normal occlusion in dogs and cats occurs when the mandibular teeth reside just lingual to the maxillary teeth and the mandibular incisor cusps rest on the cingulum on the palatal side of the maxillary incisors. In addition, the mandibular canine crowns should lie equally between the maxillary third incisor and maxillary canine. The mandibular premolar crown tips should point to the interproximal spaces between the crowns of the maxillary premolars. Each mandibular premolar should be positioned rostral to the corresponding maxillary premolar. Dogs and cats with normal occlusion generally do not have bite-related problems.

Abnormal occlusion is any presentation other than that described above. This concept creates controversy with some breeds in which mandibular mesioclusion (underbite) is considered normal (for the breed) but is often is not a healthy bite. Mandibular distoclusion (overbite) is never considered normal. Dogs and cats with abnormal occlusions (even if normal for their breed) need to be closely watched for tooth-to-tooth and tooth-to-gingiva dental trauma (see Figure 6).

Figure 6

Left maxillary canine located rostral to the mandibular canine--abnormal but functional occlusion; rechecks are indicated.

In cases where abnormal occlusion cause oral trauma, the offending tooth or teeth need to be removed (Figures 7A to 7E) or moved (Figures 8A to 8D).

Figure 7A

Left mandibular second incisor positioned in front of the maxillary incisor; removal of offending tooth is indicated.

Figure 7B

Removal of the mandibular incisor, eliminating malocclusion.

Figure 7C

Marked mandibular distoclusion resulting in the mandibular incisors and canines impinging on the maxilla.

Figure 7D

Extraction of the mandibular incisors and canines.

Figure 7E

Appearance after healing.

Figure 8A

Right maxillary canine penetrating the maxilla.

Figure 8B.

Palatal penetration from the malpositioned right mandibular canine.

Figure 8C

Moving the right maxillary canine tooth into functional position with orthodontic buttons and elastics.

Figure 8D

Functional occlusion created in four months.

In some cases of nonfunctional orthodontic disease, instead of removing the entire offending tooth, part of the crown is removed (crown reduction) then restored, which eliminates the local trauma and saves the tooth.

Endodontic diseases. Fractured teeth abound in our canine and feline patients, with the canines and carnassial teeth most commonly affected. When an affected tooth lacks periodontal support, removalis indicated. If an affected tooth has good periodontal support, treatment with either vital pulp or root canal therapy is indicated. Generally, referral to a dental specialist is necessary in these cases.

Endodontic care is largely dictated by the clinical and radiographic extent of disease at presentation, the age of the patient, and the age of the fracture. Here are some guidelines:

- Uncomplicated fractures in young animals: Restore the tooth with light-cured composite or a metallic crown.

- Uncomplicated fractures in older animals. Often no treatment is indicated if the animal is not prone to injure the tooth further.

- Uncomplicated crown-root fractures: Above steps plus care to remove the periodontal pocket; gingivectomy.

- Complicated fractures in young animals: Acute-extract or perform vital pulp therapy; chronic-extract if root canal therapy cannot be performed with a good prognosis.

- Complicated fractures in mature animals: Acute-extract or perform vital pulp therapy or root canal therapy; chronic-extract or perform root canal therapy (preferred).

Treatment workflow

Now that you know what to do, how can you fit it into the day? Much depends on how many tables and staff you have available. One approach is to perform cleaning, polishing, intraoral radiographs, probing and charting like human dentists and have the patient come back for needed treatment. The benefits of this approach include effective scheduling, discussion with the owner without pressure, and decreased initial anesthesia time. Disadvantages include failure of client compliance, resulting in patient suffering due to undelivered treatment. At my practice, we do it in one setting with a client call to explain what needs to be done once our diagnostics are reviewed.

The foundation of companion animal dental care is the tooth-by-tooth examination. Once dental abnormalities are discovered, think about the four R's-recheck, remove, repair and refer. Your patients (and their owners) will thank you.

Dr. Jan Bellows owns All Pets Dental in Weston, Florida. He is a diplomate of the American Veterinary Dental College and the American Board of Veterinary Practitioners. He can be reached at dentalvet@aol.com.