A challenging case: Lethargy and inappetence in a Pekingese

A battery of diagnostic tests were needed to uncover the root cause of lethargy, inappetence and coughing in a 7-month-old dog.

A 7-month-old 11.9-lb (5.4-kg) intact male Pekingese was presented to the Veterinary Medical Centre (VMC) at the Western College of Veterinary Medicine for evaluation of lethargy and inappetence of one week's duration and a cough of one day's duration. The owners described the cough as mild, intermittent, dry, hacking, and nonproductive.

HISTORY

The dog had vomited once seven days earlier at the onset of its signs. There was no history of trauma or previous illness.

The dog had been vaccinated in accordance with its primary veterinarian's recommendations, including receiving an intranasal Bordetella species parainfluenza vaccination. The dog had never been boarded and had not been in direct contact with other dogs aside from one housemate, a Shih Tzu.

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION AND DIAGNOSTIC TESTS

The physical examination revealed a quiet but alert dog in good body condition. Its mucous membranes were pink, and the capillary refill time was two seconds. The dog's heart rate, respiratory rate, and temperature were normal. Thoracic auscultation was normal, and the dog's femoral pulses were strong and regular. No spontaneous coughing was noted during the physical examination; however, a hacking, nonproductive cough was easily elicited on tracheal and laryngeal palpation. The remainder of the physical examination was unremarkable.

Vital Stats

An emergency panel revealed no abnormalities in packed cell volume or total protein, blood urea nitrogen, or blood glucose concentrations. Oxygen saturation, assessed by using a portable pulse oximeter, was normal (98%).

Thoracic radiography revealed a soft tissue heterogeneous opacity with central gas lucencies filling the left cranial thorax (Figure 1). No air bronchograms were visible. The trachea was deviated dorsally and mildly to the right. Cardiovascular structures were within normal limits for size and shape. The initial interpretation was that these radiographic changes could suggest a fluid-and-gas-filled cranial esophagus, abscessation and necrosis within the left cranial lung lobe, focal aspiration pneumonia, or lung lobe torsion.

1. A ventrodorsal thoracic radiograph of the 7-month-old intact male Pekingese in this report revealed a predominantly soft tissue homogeneous opacity with central gas lucencies in the region of the left cranial lung lobe. No air bronchograms are visible. The trachea deviates mildly to the right. The cardiac silhouette appears normal in size and shape.

INITIAL TREATMENT

The dog received intravenous fluid therapy and antibiotics to treat possible aspiration pneumonia. Before initiating therapy, a transtracheal wash was performed and submitted for cytologic evaluation and culture. Blood was collected for a complete blood count (CBC) and a serum chemistry profile. The dog was then treated with ampicillin (22 mg/kg intravenously q.i.d.) and amikacin (20 mg/kg intravenously once a day) as well as nebulization with water vapor and coupage every six hours.

The dog's attitude and activity improved during the first 24 hours of therapy, and it ate well in the hospital. There was no spontaneous coughing or dyspnea observed.

ADDITIONAL DIAGNOSTIC TESTS

The CBC identified a mild neutrophilia (8.4 x 109/µl; reference range = 3 to 10 x 109/µl) and a mild slightly regenerative anemia (hematocrit = 0.363 L/L [reference range = 0.365 to 0.573 L/L]; hemoglobin= 125 g/L [reference range = 128 to 196 g/L]; reticulocytes 2.6%, 1+ polychromasia). The serum chemistry profile results were unremarkable.

Transtracheal wash cytologic examination results showed a few individual and clusters of respiratory epithelial cells and rare macrophages enmeshed in mucoid material. On cytospin preparation, a moderate number of respiratory epithelial cells and erythrocytes and a few foamy macrophages were noted, some of which contained hemosiderin, suggesting ongoing intrapulmonary hemorrhage. Neutrophils were rare, no infectious organisms were noted, and the bacterial culture results were negative.

Given the lack of marked inflammation or infectious organisms, the presence of a regenerative anemia, and the identification of hemosiderophages on the tracheal wash, we considered it most likely that the patient was bleeding into the lung parenchyma. Prothrombin time and partial thromboplastin times were normal.

A radiographic examination was repeated two days after admission. The dog was clinically normal with no respiratory signs and normal appetite and activity. The opacity of the left cranial lung lobe was essentially unchanged, with subtle improvement in aeration of that lung. An ultrasonographic examination of the left cranial lung revealed no air present within the parenchyma or bronchi with little vascular supply evident, although cardiac motion interfered with Doppler detection of blood flow. No pleural fluid was evident.

The radiography and ultrasonography results together with the results of the tracheal wash made lung lobe torsion most likely. Computed tomography (CT) was recommended for further evaluation.

CT

Precontrast and postcontrast CT of the thorax with axial 1-mm slices was performed, beginning in the caudal cervical region and extending caudally to mid abdomen.

There was marked soft tissue opacification of the left cranial lung lobe and compression of the bronchus, leading to the left cranial lung lobe.

The left cranial lung lobe was larger than normal, suggesting probable vascular congestion and strongly supporting a diagnosis of lung lobe torsion.

Multiple air opacities were noted medially, which most likely represented air entrapment within bronchioles or the alveoli.

2. A postcontrast transverse image from thoracic CT of the dog in this report. Marked soft tissue opacification of the left cranial lung lobe (indicated by *) and compression of the bronchus (arrow) are noted leading to the left cranial lung lobe. The appearance of the lung tissue lateral to the opacified lung is consistent with atelectasis.

No vascular supply was noted coming into or going from the affected lung lobe; whereas, vascularity was noted in the other lung lobes (Figures 2-4). Lung lobe torsion was the probable diagnosis, and surgery was scheduled.

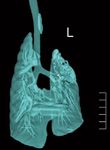

3. A 3-D reconstruction from postcontrast thoracic CT of the dog in this report. The compression and complete attenuation of the bronchus to the left cranial lung lobe is readily visible (arrow). No aeration and vascularity are visible in the left cranial lung lobe compared with the other lung lobes.

SURGICAL PREPARATION

The patient was premedicated with hydromorphone (0.1 mg/kg intravenously) and induced with alfaxalone (2 mg/kg intravenously). Before intubation, flexible bronchoscopy was performed.

4. A dorsal multiplanar reconstruction image from thoracic CT of the dog in this report. The compression and attenuation of the bronchus to the left cranial lung lobe (LCL) is clearly visible (arrow). The left cranial lung lobe is completely opacified. (The heart is labeled with an H.)

Results of the bronchoscopic evaluation of the right lung and the left caudal lung lobes were normal. The bronchi of the cranial and caudal portions of the left cranial lung lobe were twisted closed, confirming lung lobe torsion (Figure 5).

5. A bronchoscopic evaluation of the dog in this report showed a normal right lung and normal left caudal lung lobes. The bronchi of the cranial and caudal portions of the left cranial lung lobe were twisted closed (arrow), confirming lung lobe torsion.

After the bronchoscopic evaluation, the patient was prepared for surgery. The patient was intubated, and anesthesia was maintained through inhaled isoflurane and oxygen. Cefazolin (22 mg/kg intravenously) was administered after induction and continued every 90 minutes during surgery.

SURGERY

A left seventh intercostal thoracotomy was performed, which is standard procedure at the VMC. There were adhesions from the lung to the mediastinum and pericardium, which were broken down by using a LigaSure Atlas 20-cm Hand Switching Sealer/Divider Instrument (Covidien). The main bronchus and vessels supplying the left cranial lung lobe were ligated by using a TA 35 stapler (Tyco Healthcare). The lung lobe was then excised.

The pleural cavity was filled with warm sterile saline solution and observed for leaks before being lavaged several times. A chest tube was placed and directed into the cranioventral pleural space. The thoracotomy was closed in routine fashion. The chest tube was then suctioned until negative pressure was achieved.

POSTOPERATIVE CARE AND HISTOPATHOLOGY RESULTS

The patient recovered from anesthesia uneventfully. Hydromorphone (0.05 mg/kg intramuscularly every four hours) and bupivacaine 0.5% (2 ml through the chest tube q.i.d.) were administered for analgesia. Negative pressure was confirmed before instilling the bupivacaine. The chest tube was drained every six hours and removed after 24 hours.

The patient continued to do well and went home two days after surgery. No episodes of cough or respiratory distress were noted after surgery.

Numerous sections of the resected lobe were examined. Histopathologic results were consistent with lung lobe torsion, with abundant atelectasis, necrosis, hemorrhage, and thrombosis. No abnormalities in bronchial cartilage were evident.

FOLLOW-UP

The patient continued to do well four weeks after surgery, with no episodes of cough or respiratory distress.

DISCUSSION

Lung lobe torsion is a rare condition in small-animal practice. Torsion occurs when the lung rotates along the long axis, twisting the bronchovesicular pedicle at the hilus. This twist collapses the thin-walled pulmonary vein before collapsing the more muscular artery, causing pulmonary vascular congestion and consolidation of the parenchyma of the twisted lung lobe and pleural effusion.1,2

Clinical signs

Clinical signs associated with lung lobe torsion typically include dyspnea, cyanosis, coughing, weakness, lethargy, and anorexia. Less common historical findings include vomiting, diarrhea, weakness, and collapse. Signs of dyspnea related to a rapid accumulation of pleural fluid are often rapidly progressive, resulting in life-threatening respiratory distress and requiring emergency intervention.

Less commonly, dogs present for evaluation of mild or vague signs, as in this case report. This dog's cough was relatively mild, and the major reasons for its presentation for veterinary evaluation were anorexia and lethargy, which resolved with symptomatic fluid therapy. Clinical examination was largely unremarkable, and if radiography had not been performed, this dog might have been discharged from the hospital without the primary problem having been treated.

Predisposing conditions and breed predisposition

Lung lobe torsion in dogs is most often associated with predisposing conditions such as trauma, previous thoracic or abdominal surgery, diaphragmatic hernia, parenchymal disease, or pleural effusion.3 Partial collapse of a lung lobe within a pleural effusion—due to any underlying cause—may increase lung lobe mobility and lead to torsion.

Spontaneous lung lobe torsion has also been reported in dogs with no previous history of thoracic disease or trauma. Spontaneous lung lobe torsion has been reported most often in large-breed, deep-chested dogs. In this population, lung lobe torsion is most likely to affect the right middle lung lobe, presumably because of the narrow shape of that lobe and lack of attachment to surrounding tissues.2-6

Lung lobe torsion has also been reported in small-breed dogs with an apparent predisposition in young male pugs.2-10 Spontaneous lung lobe torsion has been reported in pugs 4 months to 4 years old (median age = 1.5 years).2-10 Torsion of the left cranial lung lobe is most common in small-breed dogs, including pugs.1,2,4-7,9,11 Factors contributing to spontaneous lung lobe torsion in pugs have not been determined, though bronchial cartilage dysplasia in brachycephalic breeds has been speculated to be a factor.1,4,7

Lung lobe torsion has not been commonly reported in brachycephalic breeds other than pugs, though there are two previous reports in Pekingese2,9 and English bulldogs.8,10 When evaluated, bronchial cartilage has been reported to be histologically normal in affected pugs, as it was in this Pekingese.1,4

Radiography

Thoracic radiographs of dogs with lung lobe torsion typically reveal consolidation of the affected lung lobe and pleural effusion. Pleural effusion is present in nearly all reported cases of dogs with lung lobe torsion, but as in this case, it may be absent in the early stages of this condition or in mildly affected dogs.1,2,4,7,9 Small dispersed air bubbles are commonly seen within the parenchyma of an affected lung lobe. Lobar bronchi can be visualized in about half of all cases, but recognition of the displacement of the bronchus is variable. Enlargement of the affected lobe resulting in a mediastinal shift with or without dorsal displacement of the trachea occurs in 50% of cases.1,7,9,11

Tracheal wash cytology

Tracheal wash cytology has not been previously reported in cases of dogs with lung lobe torsion. Lung consolidation in conjunction with respiratory signs, systemic signs, and sometimes fever may prompt evaluation for possible pneumonia in dogs with lung lobe torsion.

In this case, the tracheal wash cytologic examination revealed minimal inflation with ongoing hemorrhage into the lung parenchyma, presumably because of congestion. Hemoptysis and hematemesis have been reported in dogs with lung lobe torsion.9,12,13

Ultrasonography

An ultrasonographic examination of the thorax of dogs with lung lobe torsion usually reveals a pleural effusion, a densely consolidated lung lobe, and scattered reverberating foci (artifact resulting from the production of spurious echoes that are caused by reflections at the skin-transducer interface or by bone or gas) consistent with gas located centrally within the lobe.

As experienced in this case, it can be difficult to interpret Doppler detection of blood flow. The cranial mediastinum should always be evaluated for a mass, which could serve as an underlying cause for pleural effusion leading to secondary lung lobe torsion.

CT

CT is recommended in cases in which a diagnosis of lung lobe torsion is suspected but is not definitive based on radiography and ultrasonography results.4 CT findings include pleural effusion and an abrupt termination of a bronchus in the affected lung lobe. In some dogs, the bronchus will be gradually narrowed before the lumen is completely obliterated.

Other frequent findings include areas of emphysema within the affected lobe and enlargement of the affected lobe. Contrast enhancement is minimal in rotated lung lobes when compared with normally inflated and collapsed but not rotated lung lobes.10

CT images also provide information regarding abnormalities in the mediastinum and pulmonary parenchyma that could be relevant to the cause of the lung lobe torsion8 and may be helpful in surgical planning and prognosis.

Bronchoscopy

In this case, bronchoscopy was performed when the patient was anesthetized for surgery and the diagnosis was certain based on imaging results. Bronchoscopy allows visualization of the affected bronchus, which will typically appear distorted, twisted, or collapsed.7 A folded, edematous mucosa and intraluminal hemorrhage may also be seen.

Lung lobe torsion cannot be excluded as a differential diagnosis based solely on negative bronchoscopic examination results since it may be impossible to advance the bronchoscope to the level of the affected bronchus.1,5,14 Bronchoscopy is also not sufficient to determine whether an extraluminal constricting mass might be the cause of the bronchial occlusion, making CT and bronchoscopy complementary modalities for the diagnosis of lung lobe torsion.8

Treatment

The initial treatment in dogs with spontaneous lung lobe torsion consists of stabilizing their systemic and respiratory status by administering intravenous fluids, blood (if required), and inhaled oxygen and performing thoracocentesis to remove large volumes of pleural fluid.1,5 Surgical removal of the affected lobe should be performed once the patient is stabilized.

Surgical stapling is ideally suited for lung lobe torsion as the pedicle can safely be operated on in the twisted position. Derotation of the twisted lobe is contraindicated because of continued vascular congestion and endotoxin release back into the systemic circulation.

Prognosis

The prognosis for survival to hospital discharge has been described as fair to guarded, with a rate of 50% to 60% when large- and small-breed dogs are considered. Reports would suggest that the prognosis for pugs with spontaneous lung lobe torsion is more favorable, with > 85% survival and recovery with a favorable outcome.1,4,5,7

Christine Nagel, DVM, MPH* Susan Taylor, DVM, DACVIM Suresh Sathya, BVSc, MVSc Department of Small Animal Clinical Sciences Western College of Veterinary Medicine University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon, SK Canada S7N 5B4

Kim Tryon, DVM, DAVCR Department of Small Animal Radiology Western College of Veterinary Medicine University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon, SK Canada S7N 5B4

*Dr. Nagel's current address is 805 S. Jackson St., Millstadt, IL 62260.

To view the references for this article, visit dvm360.com/TorsionRefs.