CVC Highlight: Tapeworm infections: Some unusual presentations

Some important infections practitioners should be aware of.

All tapeworms of dogs and cats have an indirect life cycle. The definitive host is the host in which the tapeworm matures, reproduces, and generates eggs. The intermediate host is the one in which the metacestode (immature) form of the parasite develops. The definitive host becomes infected by eating the intermediate host, while the intermediate host becomes infected by eating eggs in an environment contaminated by the definitive host. In general, dogs and cats serve as definitive hosts, although metacestodes can sometimes develop within them.

Lora R. Ballweber, DVM, MS

TAENIA SPECIES: CYSTICERCOSIS

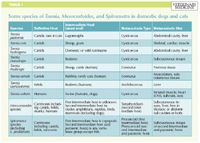

More than 60 species of Taenia species exist worldwide, many of which have canid and felid definitive hosts. For most Taenia species in the United States, the domestic definitive hosts are dogs and cats (Table 1).

Taenia species life cycles are fairly straightforward. Gravid proglottids break free of the tapeworm and are shed in the feces. Eggs are released from the segment either as it travels through the digestive tract or after it is eliminated in the feces. These eggs are then ingested by the intermediate host, the embryo hatches and migrates to its developmental site, and the metacestode develops. When the intermediate host is ingested by the definitive host, the metacestode is digested free, the scolex embeds itself in the mucosa of the small intestine, and the neck begins to grow, forming proglottids. The prepatent period is usually reported as five to 12 weeks, depending on species. How long untreated tapeworms will survive is not known for sure, but Taenia taeniaeformis has been reported to remain patent in cats for as long as 34 months.

Intestinal infections tend to be nonpathogenic. Infections are generally diagnosed based on finding proglottids in the feces, although eggs can be found on fecal flotation if a solution with the proper specific gravity is used. Praziquantel, epsiprantel, and fenbendazole are approved for the treatment of Taenia species infections in dogs and cats.

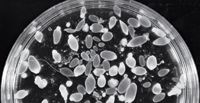

Occasionally, however, dogs and cats develop cysticercosis as a result of infection with Taenia crassiceps.1,2 The metacestode of this species of tapeworm is unique in that it is a proliferative cysticercus that develops asexually through budding (Figure 1). Consequently, ingestion of one organism or a few organisms can result in massive infections. In dogs, intraperitoneal, intrapleural, intracardiac, intracranial (also in cats), and subcutaneous (also in cats) cystcercosis have been documented, most with fatal results.1-3 Why these animals develop cysticercosis is uncertain; however, an impaired immune system is thought to play a key role.2-4 The route of infection is also speculative. Ingestion of eggs from the environment, autoinfection via eggs from gravid tapeworms within the small intestine, and ingestion of cysticerci in intermediate hosts have all been proposed. Eggs, either ingested from the environment or through autoinfection, are considered the most likely source.

Figure 1. Numerous Taenia crassiceps cyscticerci from the subcutaneous tissue of a dog.

Cysticercosis associated with T. crassiceps occurs in people as well. Although the source of infection (wild vs. domestic canid) is usually unknown, at least one case was linked to the family dog.5-8

Dogs can also develop cysticercosis as a result of infection with Taenia solium. Although now uncommon in the United States, this parasite is responsible for cerebral cysticercosis in people in many areas of the world. In these same areas, dogs can also be infected by ingesting eggs. If the cysticercus localizes to the brain, the dog can become aggressive. In developing countries where rabies is endemic, aggressive behavior is often sufficient evidence for a diagnosis of rabies, resulting in euthanasia. Therefore, dogs with cysticercosis are sometimes mistakenly thought to have rabies and are euthanized. While canine neurocysticercosis due to T. solium has not been well-recognized in the United States, it does exist in Mexico, where many rescue groups travel to bring dogs back to the United States. Current treatment recommendations include albendazole and prednisone.

SPIROMETRA SPECIES: PROLIFERATIVE SPARGANOSIS

As with other tapeworms, the life cycle of Spirometra species is indirect. However, with Spirometra species two intermediate hosts are needed rather than just one (Table 1). Mature tapeworms live in the small intestine of the definitive host; eggs are released from the proglottid and pass in the feces to the environment. If deposited or washed into water, the egg hatches and the ciliated form is eaten by a freshwater copepod crustacean. The tapeworm develops into the procercoid, which is the infective form for the second intermediate host.

Table 1: Some species of Taenia, Mesocestoides, and Spirometra in domestic dogs and cats

The second intermediate host range is quite diverse and includes most vertebrates except fish. Once ingested by the vertebrate, the tapeworm develops into another form (the plerocercoid—also called the sparganum), which is now infective to the definitive host. Conversely, if the second intermediate host is eaten by another nonfish intermediate host, the sparganum remains viable and migrates back into tissues. Within the definitive host, the sparganum remains in the small intestine where it attaches to the mucosa and matures. The prepatent period is as little as 10 days.

Intestinal infections with Spirometra species tend to cause few problems. Intermittent diarrhea or vomiting may occur. Owners may not associate these problems with tapeworm infections unless long chains of senile proglottids are found. Eggs can be found on fecal flotation but are very similar to those of Diphyllobothrium species. Praziquantel is the treatment of choice for this parasite infection.

Dogs can also act as second intermediate hosts of Spirometra species if they drink water with infected copepods. In these cases, which have mostly been reported in the Deep South, the spargana develop within the tissues of the dog. Sparganosis can be proliferative or nonproliferative. Most infections are nonproliferative, such that ingestion of a single procercoid results in the development of a single plerocercoid. But in proliferative sparganosis, ingestion of a single procercoid can result in numerous spargana as a result of the asexual replication of the larvae. The larvae grow and repeat the process, which can ultimately lead to death of the host.9

Clinical signs of nonproliferative sparganosis are the presence of subcutaneous nodules or cysts. For proliferative sparganosis, the most recent report in a dog indicated initial signs were progressive forelimb lameness and pain associated with subcutanous cysts.9 As the condition deteriorated, fever, dyspnea, mature neutrophilia and hypoproteinemia were present. At necropsy, numerous cysts were found in the soft tissues of the forelimb and neck as well as within the pleural and peritoneal cavities.9

In domestic animals, no approved treatment for sparganosis is available. Various anthelmintics have been tried, most with poor results. The lack of treatment options for proliferative sparganosis generally warrants a poor prognosis for survival.

MESOCESTOIDES SPECIES: CANINE PERITONEAL LARVAL CESTODIASIS

Although Mesocestoides species were first described in 1863, we still do not know the complete life history of these parasites. Species of Mesocestoides occur worldwide. Mature tapeworms live in the small intestine of a variety of birds and mammals, including domestic dogs and cats (Table 1). It appears that some type of coprophagous invertebrate is the most likely first intermediate host. The typical metacestode stage, the tetrathyridium, occurs within the second intermediate host, which includes amphibians, reptiles, birds, and mammals. These tetrathyridia tend to localize within the peritoneal cavity, lungs, and liver. When eaten by the definitive host, they mature in 16 to 21 days. Certain strains of the parasite can asexually reproduce within the intestinal tract of the definitive host as well as within the tissues of the intermediate host. One study showed that ingestion of 500 tetrathyridia could result in as many as 17,000 mature tapeworms in the dog.

Intestinal infections in the definitive host are not usually associated with clinical signs. However, dogs and cats can also serve as second intermediate hosts, and infection in dogs can lead to a condition called canine peritoneal larval cestodiasis (CPLC). Clinical signs of CPLC range from none to abdominal enlargement, ascites, anorexia, vomiting, and peritonitis. Ascites is the most common presenting sign, followed by anorexia and weight loss. CPLC is an incidental finding in approximately one-fourth of all cases.10-12

CPCL is a life-threatening disease with a guarded prognosis. The most significant factors influencing survival are the severity of clinical signs at the time of diagnosis and application of an aggressive treatment strategy after diagnosis. The most effective approach appears to be a combination of surgery and anthelmintic treatment. Regardless of the treatment approach, the prognosis is guarded, especially for dogs presenting with rapidly developing signs or severe disease.10

Peritoneal lavage or surgical removal of cysts is recommended before the initiation of anthelmintic therapy, especially in cases where large volumes of fluid and parasites are present. The current suggested anthelmintic treatment is fenbendazole at 100 mg/kg orally, twice daily for 28 consecutive days.10 It may be necessary to re-treat animals if clinical disease reoccurs in the months or years following initial treatment. Praziquantel (5 mg/kg) is used to treat mature, intestinal infections with good results.

Lora R. Ballweber, DVM, MS

Department of Microbiology, Immunology and Pathology

College of Veterinary Medicine & Biomedical Sciences

Colorado State University

Fort Collins, CO 80523-1644

REFERENCES

1. Ballweber LR. Taenia crassiceps-associated subcutaneous cysticercosis in an adult dog. Vet Rec 2009;165:693-694.

2. Wünschmann A, Garlie, V, Averbeck G, et al. Cerebral cysticercosis by Taenia crassiceps in a domestic cat. J Vet Diagn Invest 2003;15:484-488.

3. Hoberg EP, Ebinger W, Render AJ. Fatal cysticercosis by Taenia crassiceps (Cyclophyllidea: Taeniidae) in a presumed immunocompromised canine host. J Parasitol 1999;85:1174-1178.

4. Chermette R, Bussiéras J, Biétola E, et al. Quelques parasitoses canines exceptionnelles en France. III—Cysticercose proliférative du chien à Taenia crassiceps: à propos de trois cas. Pratique Médicale Chirurgicale l'Animal Compagnie 1996;31:125-135.

5. Freeman RS, Fallis AM, Shea M, et al. Intraocular Taenia crassiceps (Cestoda) Part II. The parasite. Am J Trop Med Hyg 1973;22:493-495.

6. Aghamohammadi S, Yoken J, Lauer AK, et al. Intraocular cysticercosis by Taenia crassiceps. Retinal Cases Brief Reports 2008;2:61-64.

7. Heldwein K, Biedermann H-G, Hamperl W-D, et al. Subcutaneous Taenia crassiceps infection in a patient with non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2006;75:108-111.

8. Maillard H, Marionneau J, Prophette B, et al. Taenia crassiceps cysticercosis and AIDS. AIDS 1998;12:1551-1552.

9. Drake DA, Carreño AD, Blagburn BL, et al. Proliferative sparganosis in a dog. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2008;233:1756-1760.

10. Boyce W, Shender L, Schultz L, et al. Survival analysis of dogs diagnosed with canine peritoneal larval cestodiasis (Mesocestoides spp.). Vet Parasitol 2011; E-pub ahead of print.

11. Caruso KJ, James MP, Fisher D, et al. Cytologic diagnosis of peritoneal cestodiasis in dogs caused by Mesocestoides sp. Vet Clin Pathol 2003;32:50-60.

12. Toplu N, Yildiz K, Tunay R. Massive cystic tetrathyridiosis in a dog. J Small Anim Pract 2004; 45:410-412.