Hot Literature: Antibiotic guidelines for dogs and cats with urinary tract disease

These guidelines may help counteract the rise in antibacterial resistance as well as lessen the overall impact of misuse on patient health.

Antimicrobial use guidelines are currently used in human medicine to provide guidance to doctors when selecting drugs to treat a variety of conditions. These guidelines have been instituted to help counteract the rise in antibacterial resistance as well as lessen the overall impact of misuse on patient health. In 2010, the Antimicrobial Guidelines Working Group of the International Society for Companion Animal Infectious Diseases began developing guidelines that may be used to treat dogs and cats with urinary tract diseases. These guidelines are given as general recommendations to aid in the decision-making process. An overview is provided here; to read the complete guidelines, visit http://hindawi.com/journals/vmi/2011/263768

Andreas Reh/Getty Images.

SIMPLE, UNCOMPLICATED UTIs

By definition, these urinary tract infections (UTIs) occur in patients that are otherwise in good health and that have had fewer than three previous UTIs in a 12-month period.

Diagnosis

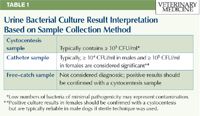

Clinical signs (dysuria, pollakiuria, increased urgency) as well as bacteriuria and pyuria should be present. A complete urinalysis along with sediment evaluation is recommended in all cases, along with aerobic bacterial culture and susceptibility testing. The urine sample should be kept refrigerated, and the culture should be performed within 24 hours of collection. Interpretation of the urine culture results will vary based on the sample collection method (Table 1).

Table 1: Urine Bacterial Culture Result Interpretation Based on Sample Collection Method

Treatment

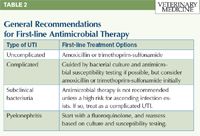

Initial therapy in most of these patients should consist of amoxicillin or trimethoprim-sulfonamide while you await culture results (Table 2). Clinicians should monitor changes in local resistance patterns in patients with uncomplicated UTIs that may necessitate a change in first-line drug choices.

Table 2: General Recommendations for First-line Antimicrobial Therapy

If a patient demonstrates clinical improvement while receiving the initial therapy despite in vitro resistance based on sensitivity testing, the current treatment should be continued, and a follow-up urinalysis and culture should be performed after the treatment is completed.

If there is no response to treatment and the isolate is resistant to the initial drug choice, an alternative drug should be selected.

Treatment for seven days with appropriate antimicrobials is reasonable for these patients, and monitoring only requires resolution of clinical signs.

COMPLICATED UTIs

Patients with complicated UTIs are those with concurrent medical illnesses or anatomic or functional abnormalities that predispose them to persistent infection ( e.g. bladder stones, diabetes, neurogenic bladder). Three or more UTIs a year also indicate complicated infection. In patients with recurrent infection, determining whether the current episode is a reinfection or a relapse may be important in determining therapy. Reinfection is defined by isolation of a new organism within six months of the previous episode. If the same organism is isolated, a relapse is more likely, probably due to failure to eliminate the organism initially.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is the same as for uncomplicated UTIs, and bacterial cultures should be performed in all cases to confirm. Investigation into complicating factors that may be predisposing a patient to infection should be undertaken (complete blood count, serum chemistry profile, abdominal imaging, and possible endocrine testing) in addition to urinalysis and culture. A thorough physical examination is required, and, in some instances, referral for more advanced testing such as cystoscopy may need to be considered.

Treatment

If possible, treatment should be delayed until the culture results are available (Table 2), and preference should be given to those drugs that are excreted in the urine in an active form. Additionally, while drugs that the bacteria are resistant to should be avoided, those drugs classified as intermediate may still be considered if they are known to achieve high concentrations in the urine or if the dosage can be increased.

In those cases in which more than one organism is isolated in the culture, consider bacterial counts and the pathogenicity of each organism when devising a treatment plan. Combination drug therapy may be needed in some cases. No evidence in the veterinary literature supports the use of clarithromycin to break down bacterial biofilm or the use of direct instillation of antimicrobials or antiseptics into the bladder.

The duration of treatment for these patients will vary, but four weeks is a reasonable starting point. In those patients with underlying diseases that can be controlled or cured, shorter therapy may be considered.

Response to therapy should be assessed with bacterial cultures performed five to seven days after the initiation of therapy. Positive culture results during treatment will require reevaluation and referral, or consultation with a specialist should be considered.

A repeat urine culture should be performed seven days after the end of therapy. If the culture result is still positive, further evaluation and referral should be recommended.

The working group does not recommend the use of either pulse therapy or chronic low-dose therapy to prevent UTIs in these patients as there is no evidence to support this practice. Nutritional supplements such as cranberry juice have shown some benefit in preventing UTIs in people, but no supportive data exist in veterinary medicine.

SUBCLINICAL BACTERIURIA

Patients with subclinical bacteriuria have a positive urine culture result but demonstrate no clinical signs or cytologic evidence and may not require therapy (even in the face of multidrug-resistant organisms). Treatment should be considered, however, if a patient is at risk of infection such as those patients that are immunocompromised or have renal impairment.

URINARY CATHETERS

Patients with indwelling urinary catheters do not require prophylactic antimicrobial therapy. Treatment of these patients is only indicated if there are clinical signs or cytologic evidence supportive of infection. In that case, treatment should be based on culture and sensitivity data.

Routine culture of the catheter tip or urine at the time of catheter removal is not recommended. In those patients in which there is a high risk for or significant consequence to a UTI, culture of a sterilely collected urine sample is recommended.

UPPER UTIs (PYELONEPHRITIS)

Diagnosis of upper UTIs is similar to that of other UTIs described above. Treatment should be determined based on serum susceptibility data rather than urine concentrations, and initial therapy should target gram-negative organisms since they are commonly involved in these infections. Fluoroquinolones are a reasonable first choice while culture results are pending. Treatment for four to six weeks is often required. As for complicated UTIs, cultures should be repeated one week after starting therapy and again one week after termination of therapy to ensure elimination. If continued infection or multidrug-resistance is noted, consultation with a specialist is indicated.

MULTIDRUG-RESISTANT INFECTIONS

The incidence of multidrug-resistant organisms is growing and may be a reflection of inappropriate antimicrobial therapy leading to the emergence and dissemination of these pathogens. Because of limited drug choices available to treat these infections, drugs that are important in human medicine are sometimes required. The use of these drugs (i.e. vancomycin, carbapenems, and linezolid), however, is not justified unless these criteria are met:

1. Infection must be documented based on clinical signs, cytologic abnormalities, and culture results.

2. There are no other reasonable antimicrobial options to which the organism is sensitive, and susceptibility to the chosen drug is documented.

3. These drugs should not be used in cases in which there is not a realistic chance of eliminating the infection.

4. Consultation with a specialist must be obtained to evaluate whether there are any other viable options and whether treatment is advisable.

Weese JS, Blondeau JM, Boothe D, et al. Antimicrobial use guidelines for treatment of urinary tract disease in dogs and cats: Antimicrobial Guidelines Working Group of the International Society for Companion Animal Infectious Diseases. Vet Med Int 2011;2011;263768. Epub 2011 Jun 27.

This "Hot Literature" update was provided by Jennifer L. Garcia, DVM, DACVIM, a veterinary internal medicine consultant in Houston, Texas.

Urinalysis offers a noninasive, rapid screening for canine cancer detection

February 9th 2024This is the first rapid test using urine developed by the Virginia Tech College of Engineering, College of Agriculture and Life Sciences, and the Virginia-Maryland College of Veterinary Medicine

Read More

Sweet pee new remedy in feline diabetes

November 9th 2023A novel class of drugs normalizes blood glucose in type 2 diabetic cats by dumping sugar into urine rather than modulating glucose uptake in the tissues but patient selection and close monitoring are crucial to using them safely

Read More