Putting the preventive into flea allergy dermatitis

Advice to allay "Just what am I giving my pet?" veterinary client concerns about flea control products.

An important part of treating a pet allergic to fleas is keeping the pet on year-round flea control. But you've likely encountered owners who have expressed concern they'll be giving their pets an insecticide-whether orally or topically-and they say, "That can't be safe!" To calm their fears, explain the following.

Flea preventives exploit a difference in the nervous system between insects and mammals.1,2 It is anatomically and physiologically impossible for these products to kill a mammal the same way they kill fleas. Adverse reactions may occur, as they can with any oral or topical product of any kind, but they're typically not serious and the benefits far outweigh the risks.

Point out that consistent, routine administration schedules of these preventives vary and some products are formulated for longer duration of action (e.g. 12 weeks); plus, flea prevention is a lot safer than repeated courses of corticosteroids and antibiotics to manage the clinical signs of flea allergy dermatitis. Explain that most adverse reactions in pets and people, such as drooling, vomiting, tremoring, hyperexcitability, seizures, weakness and paresthesia (a tingling sensation), involve topical products containing pyrethrins or older organophosphates and carbamates.3,4 Many clients do not realize that when these adverse events are documented it does not note if the product was applied in the correct manner and in the labeled species. Despite the package warnings, pyrethrins are still being applied to cats, which contributes to these adverse events.

Although many approved veterinary products are systemically absorbed and have been deemed safe and effective by the FDA, some owners still have a fear of any orally administered insecticide. Sometimes despite education there is still a hesitation and these clients may feel more comfortable with a topically applied product. Some topical products, such as imidacloprid, are not systemically absorbed and may better suit this type of owner.

While dermal hypersensitivity reactions can occur, point out that this is also true with any soap or lotion we would use on ourselves. Many dermal reactions are related to carrier ingredients rather than the active ingredient.4 The risk to the people in the household is minimal, and the reactions depend on the ingredients present in the medication. Thorough washing of your hands after administration of any pesticide is recommended to decrease exposure to the product and topical irritancy.

If the allergic effects aren't enough to convince owners of flea-allergic pets to routinely provide flea control, inform clients of the diseases that can be caused and transmitted by fleas.5,6 These include iron deficiency anemia and infection with Rickettsia typhi, Rickettsia felis, Bartonella henselae, Mycoplasma haemofelis, Yersinia pestis (that's the plague!) and Dipylidium caninum.

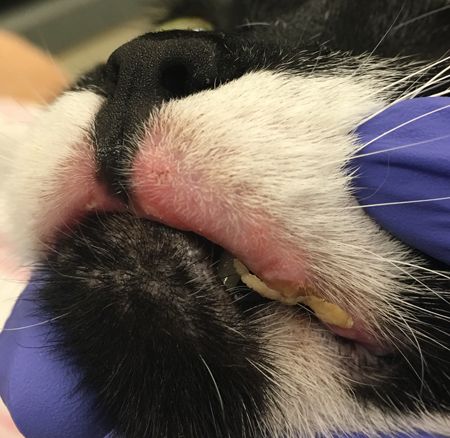

The dermatologic effects of flea allergy dermatitis are evident in this cat, but let's look a little closer ...

Notice the adult tapeworm (Dipylidium caninum) in the cat's mouth! (Photos courtesy of Christina Restrepo, DVM, DACVD, Naples, Florida)

Educate owners that these diseases are worse than flea infestation and may require treatment that is less safe than prescription flea preventives. Use of the broader term “parasites” can sometimes invoke greater willingness of the owner.

References

1. Tomizawa M, Casida JE. Neonicotinoid insecticide toxicology: mechanisms of selective action. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 2005;45:247-268.

2. Vo DT, Hsu WH, Abu-Basha EA, et al. Insect nicotinic acetylcholine receptor agonists as flea adulticides in small animals. J Vet Pharmacol Ther 2010;33:315-322.

3. Caloni F, Cortinovis C, Rivolta M, et al. Suspected poisoning of domestic animals by pesticides. Sci Total Environ 2016;539:331-336.

4. Wismer T, Means C. Toxicology of newer insecticides in small animals. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 2012;42:335-347, vii-viii.

5. Rust MK, Dryden MW. The biology, ecology, and management of the cat flea. Annu Rev Entomol 1997;42:451-473.

6. Dryden MW. Flea and tick control in the 21st century: challenges and opportunities. Vet Dermatol 2009;20:435-440.