Recognizing and treating ProMeris-triggered pemphigus foliaceus in dogs

Read this report of the successful treatment of two dogs.

Pemphigus foliaceus is the most common autoimmune skin disease in dogs.1 Canine pemphigus foliaceus typically manifests as bilaterally symmetrical pustules and erosions and crusts on the face and ears. Occasionally, lesions also develop on the footpads, around the claws, or on the trunk.1

People and dogs affected with pemphigus foliaceus produce autoantibodies that target desmosomes, the structures responsible for cell-to-cell adhesion within the epidermis.1 As a result of autoantibody binding, cells of the superficial epidermal layers lose their attachment to neighboring keratinocytes, and they round up and become the so-called acantholytic cells. Superficial epidermal clefting with pustule formation then ensues.

Genetic and environmental factors, as well as drug administration, are suspected to lead to the development of canine pemphigus foliaceus.1 Since the 1990s, various drugs have been reported as a possible cause of canine pemphigus foliaceus,2-4 but in these cases, only rarely was a direct drug-disease relationship proved.

Recently, we reported that 22 dogs treated with a novel topical flea and tick preventive that contains metaflumizone and amitraz (ProMeris Duo [Fort Dodge Animal Health, later acquired by Pfizer Animal Health], marketed as ProMeris for dogs in the United States) all subsequently developed pemphigus foliaceus-like skin lesions at the application site.5 In all of these cases, the earliest skin lesions were noticed between the shoulder blades, which is not a predilection site for typical spontaneously arising autoimmune pemphigus foliaceus. Moreover, in two-thirds of these dogs, skin lesions eventually became generalized.5 Most dogs with generalized skin disease have signs of systemic illness, and they require variable immunosuppressive regimens similar to those given to dogs with spontaneous autoimmune pemphigus foliaceus. Generalized ProMeris-triggered pemphigus foliaceus cannot be distinguished from spontaneously occurring autoimmune pemphigus foliaceus clinically or by histopathology or autoantibody detection tests.5

Since some dogs with ProMeris-triggered pemphigus foliaceus develop more severe signs after each subsequent drug application, veterinary practitioners must recognize this unusual form of pemphigus foliaceus as early as possible. Once this drug-disease relationship is established, application of the preventive must be stopped to prevent further disease progression, and anti-inflammatory or immunosuppressive treatment should be initiated.

In this article, we discuss two dogs with ProMeris-triggered pemphigus foliaceus that we successfully treated. In both cases, the lesions initially presented at the preventive application sites and then extended to distant skin areas to become generalized. In addition to these cases, we also provide information on the prognosis and management of this disease in general.

CASE #1

A 7-year-old female spayed Labrador retriever was presented to the North Carolina State University (NCSU) Veterinary Teaching Hospital Dermatology Service for evaluation of skin lesions and lameness of two weeks' duration.

History

Ten months before the referral, the dog's monthly flea and tick prevention was changed from Frontline (Merial) to ProMeris. The patient had received a total of three ProMeris applications—the first two three months apart and the third five months later.

One month after the third application, the owner noticed extensive crusting on the application site between the shoulder blades and lameness of the left front leg. The dog was examined by its primary-care veterinarian who suspected that a tick-borne disease caused the lameness. Doxycycline and cefazolin were prescribed. Skin biopsy samples were taken from interscapular crusts, and histologic examination revealed an acantholytic dermatosis of unknown origin.

The patient's health worsened dramatically over the following days. The dog appeared to be in pain and showed lameness of the left front paw, and the skin lesions progressed. The veterinarian subsequently administered a single injection of dexamethasone sodium phosphate (0.13 mg/kg) and cefovecin. Additionally, he prescribed prednisone (1 mg/kg twice daily) and tramadol and applied a transdermal fentanyl patch; the doxycycline was continued. Only minimal improvement of the lameness and skin lesions was seen with this regimen, so the dog was referred to NCSU.

Dermatologic examination

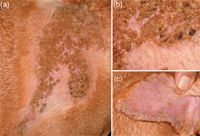

At presentation to the dermatology service, the patient was in good general health aside from its left front leg lameness and extensive skin lesions. The dermatologic examination revealed a 30-x-30-cm area of crusting in the interscapular region that extended down the shoulder blades (Figures 1A & 1B). Crusts were also evident on the concave aspects of both pinnae (Figure 1C), and hyperkeratosis was noted on the footpads on the left front foot, possibly suggesting previous epithelial damage.

Cytologic examination of purulent exudate obtained from a crusted lesion on the shoulder revealed neutrophils and acantholytic keratinocytes suggestive of pemphigus foliaceus. The original biopsy samples were requested for review. Serum was collected for detection of circulating antikeratinocyte autoantibody by indirect immunofluorescence in the NCSU laboratory.

Figure 1A-1C. The patient in Case #1 at presentation: 1A) The lesions at the ProMeris application site (the area is partially shaved). 1B) A close-up of this region reveals severe crusting, mild erythema, and shallow erosions underneath these crusts. 1C) In addition to lesions at the preventive application site, crusts, mild erythema, and scaling were discovered on the concave aspects of the pinnae.

Diagnosis and treatment

Pending the histologic examination and immunologic testing results, and based on the strong suspicion of ProMeris-triggered pemphigus foliaceus, the glucocorticoid was changed to prednisolone, and the dose was increased to 1.5 mg/kg twice daily, while tramadol was to be given as needed to relieve pain.

The results of the histologic examination confirmed the presence of superficial epidermal neutrophilic pustular dermatitis with keratinocyte acantholysis. Bacteria or dermatophytes in the stratum corneum were not seen by using special stains. Direct immunofluorescence performed on paraffin-embedded skin sections revealed intercellular deposits of IgG and IgM in lesional and perilesional epidermis. Circulating antikeratinocyte autoantibodies were not detected at a 1:20 serum dilution.

All together, the dog's history, clinical signs, and results of cytologic and histologic examinations and direct immunofluorescence testing were highly suggestive of a diagnosis of ProMeris-triggered pemphigus foliaceus.

Follow-up

The dog returned for a reevaluation the next week. The skin lesions had markedly improved—only minor crusting was present in the interscapular region and pinnae. The dog no longer exhibited signs of lameness, and the tramadol was discontinued. The prednisolone dose was tapered over the next 11 days, and the disease has remained in remission without any relapse for more than two years. The dog subsequently began to receive Frontline Plus (Merial) as a topical flea and tick preventive. This product was well-tolerated, and no recurrence of the skin lesions was reported by the owner.

CASE #2

A 9-year-old spayed female large mixed-breed dog was presented to NCSU for evaluation of progressive skin lesions of eight months' duration.

History

At the time of lesion onset, the dog's monthly topical flea and tick prevention had been changed from Frontline (Merial) to ProMeris. Since then, the owner had observed crusts between the shoulder blades within days of each ProMeris application, starting with the first one. The lesions were initially restricted to the application site and always resolved within two days without any treatment. However, with each subsequent application, the affected area grew in size, and, eventually, it was no longer confined to the interscapular region.

Within hours after the seventh application, the patient became lethargic and anorectic, was chewing at its paws, and had extensive crusting between the shoulder blades. The dog was subsequently hospitalized at an emergency clinic for two days of intravenous fluid therapy. After initial improvement of the lethargy, the patient developed a fever of 104.9 F (40.5 C) and became lethargic again; this time, the patient was also lame on all four legs. The skin lesions spread to involve the ventral abdomen, flank regions, paws, and pinnae.

The primary-care veterinarian prescribed a four-day course of oral antibiotics and administered an intravenous injection of dexamethasone (0.16 mg/kg). This combination resulted in improvement of the lethargy and resolution of the lameness; however, the skin lesions remained, and the dog was referred to NCSU.

Dermatologic examination

At presentation, the dog was found to be in good general health with a temperature of 101.5 F (38.6 C). Large pustules and severe crusting extended from the product application site down to the lateral thorax (Figure 2) and both front legs but also spread to areas distant from the application site. Lesions were seen bilaterally on the pinnae, interdigital spaces of all four paws, the ventral abdomen, and flanks. Pustules and crusts were surrounded by moderate erythema (Figure 2).

Figure 2. In the dog in Case #2, matted crusts were found over the shoulder region; the hair was clipped in this area. The arrangement of these skin lesions, in a saddle-like pattern possibly related to the dissemination of the preventive over the dog's body, is unique. In addition to these lesions, grouped intact pustules with peripheral erythema (arrowheads) were seen between the digits in this patient (inset). These pustules were rich in acantholytic keratinocytes.

Microscopic examination of the content of a superficial pustule revealed neutrophils, eosinophils, and acantholytic keratinocytes and was suggestive of pemphigus foliaceus. Skin biopsy samples were obtained for histologic examination and direct immunofluorescence testing. Serum was collected for circulating antikeratinocyte autoantibody detection by indirect immunofluorescence testing.

Diagnosis and treatment

Pending biopsy results, and because of the strong clinical suspicion of ProMeris-triggered pemphigus foliaceus, prednisolone (0.8 mg/kg orally twice daily) was administered.

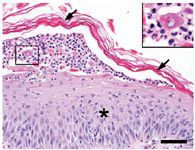

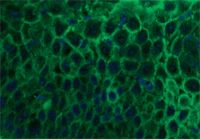

Histologic examination results showed intraepidermal pustules with large numbers of acantholytic cells and neutrophils typical of canine pemphigus foliaceus (Figure 3). Superficial epidermal fungal or bacterial organisms were not identified by using special stains (periodic acid-Schiff and Gram's, respectively). Direct immunofluorescence testing revealed intercellular deposits of IgG (Figure 4) and IgM in the superficial layers of lesional epidermis.

Figure 3. Histologic changes of ProMeris-triggered pemphigus foliaceus mirror those of naturally occurring pemphigus foliaceus. The stratum corneum (arrows) lifts away from the hyperplastic epidermis (asterisk) during formation of a subcorneal pustule that contains neutrophils and acantholytic keratinocytes (box inset) (hematoxylin-eosin stain; bar = 50 µm).

Serum antikeratinocyte IgG autoantibodies were not detectable by indirect immunofluorescence testing.

Figure 4. Direct immunofluorescence revealed the presence of IgG (green) deposited in an intercellular pattern between epidermal keratinocytes (blue nuclei) (IgG-fluorescein, DAPI nuclear counterstain).

In this case, the historical use of ProMeris and the subsequent development of an acantholytic pustular dermatitis originating from the application site in the absence of microorganisms were consistent with a diagnosis of generalized ProMeris-triggered pemphigus foliaceus.

Follow-up

The patient returned for reevaluation 11 days after the initial presentation to NCSU. The dog was still receiving 0.8 mg/kg prednisolone twice daily, and the dermatologic examination revealed only minor dry and peeling crusts with no new pustules or erythema surrounding them. The patient was in good general health, and the prednisolone was tapered.

Over the next two weeks, the patient's ProMeris-triggered pemphigus foliaceus went into complete remission, its lameness resolved, and the prednisolone was discontinued. The patient began to receive monthly topical flea and tick prevention, using either Frontline Plus (Merial), Advantage (Bayer Animal Health), or, most recently, Vectra 3D (Summit VetPharm) on an alternate basis. A recurrence of the skin lesions was not reported by the owner, and this dog's disease has remained in remission for more than 27 months.

DISCUSSION

In dogs, spontaneously arising autoimmune pemphigus foliaceus typically begins and manifests with bilateral, symmetrical, pustular, erosive, and crusted lesions on the face and ears, while pedal or generalized lesions are seen in fewer patients.1 In contrast, as was shown in these two cases, ProMeris-triggered pemphigus foliaceus is unique in that lesions will first appear in the interscapular region—the usual site of ProMeris application—an area rarely affected by lesions of naturally occurring pemphigus foliaceus.5 As a result, it is important to obtain information about the first location of skin lesion development as it will help you differentiate natural pemphigus foliaceus from contact ProMeris-triggered pemphigus foliaceus.

Lesions of ProMeris-triggered pemphigus foliaceus can arise after the first application, but it usually takes more than one dose (up to eight in our series in some cases) for lesions to develop.5 Crusts are usually seen within 14 days of product application.

Signalment

In our series of 22 dogs with ProMeris-triggered pemphigus foliaceus,5 most patients were older than 6 years of age, female, and heavier than 44 lb (20 kg). Even though a reference population was not available because of their diverse geographic origin, these observations suggest a higher risk of development in female dogs of large breeds, such as Labrador and golden retrievers, or it could merely reflect the higher usage of this product in large-breed dogs.5

Disease types

Two patterns of ProMeris-triggered pemphigus foliaceus have so far been identified: contact and generalized.5

Contact. In one-third of dogs with ProMeris-triggered pemphigus foliaceus, lesions are restricted to or extend from the application site on the proximal dorsal trunk, and systemic signs are seen in only one-third of these dogs.

The cutaneous histopathologic lesions in dogs with localized contact ProMeris-triggered pemphigus foliaceus are similar to those of autoimmune pemphigus foliaceus. In a previous study, skin-fixed antikeratinocyte autoantibodies were revealed in only half of the dogs, while similar autoantibodies were normally not detected in the serum of affected individuals by using indirect immunofluorescence testing.

Localized ProMeris-triggered pemphigus foliaceus has a favorable prognosis with complete remission seen in all dogs, but sometimes only after months of topical or systemic anti-inflammatory or immunosuppressive drugs. Medications can normally be stopped, without relapses, once lesions have resolved.5

Generalized. In two-thirds of dogs with ProMeris-triggered pemphigus foliaceus, lesions start at the application site, but at some point, lesions also erupt at areas distant from these initial sites.5 In this group of dogs, lesions are seen at body areas typically affected by lesions of spontaneous autoimmune pemphigus foliaceus, such as the ears, face, nose, trunk, and feet. Systemic signs (e.g. lethargy, anorexia, fever, lameness) are seen in three-fourths of these dogs.

In these cases, lesions at application sites and areas distant from it are not microscopically different from those of typical autoimmune pemphigus foliaceus. Furthermore, antikeratinocyte autoantibodies are detected in the skin and serum of most of these patients.

In most dogs with generalized lesions, treatment with glucocorticoids alone or with additional immunosuppressive drugs (e.g. azathioprine, cyclosporine) is needed to induce remission, which is not obtained in all patients. Some dogs require long-term treatment with immunosuppressants, and lesions may recur when the doses are decreased.

CONCLUSION

The two dogs described in this article had histories and skin lesions typical of those of generalized ProMeris-triggered pemphigus foliaceus. In both dogs, oral prednisolone administered at immunosuppressive doses led to the progressive disappearance of skin lesions, the eventual cessation of treatment, and a lack of disease recurrence after glucocorticoid withdrawal. This rapid positive response to treatment is unusual for dogs with generalized ProMeris-triggered pemphigus foliaceus, which typically requires prolonged immunosuppressive therapy. In these two dogs, the excellent outcome might be related to the lack of detectable serum autoantibodies, which suggests that a systemic antikeratinocyte autoimmune response, if present, might have been mild or transient.

Our observations argue for the early recognition of interscapular lesions and evaluation of their association with a previous application of ProMeris. Once ProMeris-triggered pemphigus foliaceus is diagnosed, it is crucial to stop application of ProMeris, wash the area, and immediately start treatment with topical or oral glucocorticoids depending on lesion severity (see the Related Link below titled "How to manage suspected cases of ProMeris-triggered pemphigus foliaceus" this issue).

If lesions are seen at body areas distant from the product application site, then the patient should be considered as having a ProMeris-triggered autoimmune disease that mirrors spontaneous pemphigus foliaceus. In these cases, and pending additional information, diagnostic procedures and treatment are recommended to be similar to those for natural pemphigus foliaceus.

To the best of our knowledge, similar reactions have not been reported in cats with the ProMeris formulation that contains metaflumizone.

Editors' Note: In April, Pfizer Animal Health announced that it has decided to discontinue the distribution of ProMeris by the fall.

Ursula Oberkirchner, DrMedVet

Thierry Olivry, DrVet, PhD, DACVD, DECVD

Department of Clinical Sciences

College of Veterinary Medicine

North Carolina State University

Raleigh, NC 27606

Keith Linder, DVM, PhD, DACVP

Department of Population Health and Pathobiology

College of Veterinary Medicine

North Carolina State University

Raleigh, NC 27606

REFERENCES

1. Olivry T. A review of autoimmune skin diseases in domestic animals: I - superficial pemphigus. Vet Dermatol 2006;17:291-305.

2. Medleau L, Shanley KJ, Rakich PM, et al. Trimethoprim-sulfonamide-associated drug eruptions in dogs. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 1990;26:305-311.

3. Noli C, Koeman JP, Willemse T. A retrospective evaluation of adverse reactions to trimethoprim-sulphonamide combinations in dogs and cats. Vet Q 1995;17:123-128.

4. White SD, Carlotti DN, Pin D, et al. Putative drug-related pemphigus foliaceus in four dogs. Vet Dermatol 2002;13:195-202.

5. Oberkirchner U, Linder KE, Dunston S, et al. Metaflumizone-amitraz (Promeris)-associated pustular acantholytic dermatitis in 22 dogs: evidence suggests contact drug-triggered pemphigus foliaceus. Vet Dermatol 2011;Mar 21. [Epub ahead of print].