TCC: When Gotta go, gotta go, gotta go right now is a malignant matter

Dr. Kim Johnson shares tips on diagnosing and treating canine transitional cell carcinoma.

Scottish terriers are 21 times more likely to get TCCs than other breeds. (Konstantin / stock.adobe.com)

Transitional cell carcinoma (TCC) of the urinary bladder, the most common malignancy of the urinary tract in dogs, is challenging to both diagnose and treat effectively. In her talk at Fetch dvm360, Kim Johnson, DVM, DACVIM, laid out some tips that may help you with this challenging cancer.

What causes TCCs?

Dr. Johnson says we don't really know. It's possible that environmental pollution, chemicals and obesity all have a role to play. Dogs that are obese, female and above 9 years of age are most likely to get TCCs, although males can get them as well. Scottish terriers are 21 times more likely to get TCCs than any other breed.1-6 Signs of the cancer include hematuria, pollikauria, stranguria and tenesmus.

Presenting complaints are not just limited to the urinary tract! Lameness can also be a clinical sign, since the cancer can spread to bone. You may also see some improvement clinically after treating with antibiotics and anti-inflammatories, but signs will return once treatment is stopped, and meanwhile the tumor may be growing during this time.

How do you diagnose TCCs?

Diagnostic tip:

To increase your sample size for cytology, traumatic/diagnostic catheterization can be performed where the catheter is inserted and then pushed around onto the bladder walls to try and get cells to dislodge into the urine. Dr. Johnson says this is OK to do and not to worry about spreading the cancer, especially when it comes to cystocentesis or fine-needle aspirates (FNA) of the bladder. She says, “It's OK! Do the FNA! Back in the good ole days, we did cystocenteses and other diagnostics without the benefit of ultrasound. I'm confident several of those bladders had TCC and we didn't know it.”

Always do a rectal exam! You may feel a mass or an enlarged prostate in males, and a cobblestone urethra may be palpated.

Diagnostics for the condition include baseline hematology (a complete blood count and a serum chemistry profile), urinalysis and culture, abdominal and chest radiographs, and abdominal ultrasound and advanced imaging when possible.

These methods may help with early detection:

Veterinary bladder tumor antigen (VBTA). This test detects tumor analytes in the urine. It has a high diagnostic sensitivity (about 90%), meaning TCC is unlikely in a dog with a negative result. However, Dr. Johnson doesn't currently recommend this test, because it's only moderately diagnostically sensitive (approx. 78-85%), meaning there may be false positives due to glucosuria, pyuria or hematuria. So Dr. Johnson says that with this test, you will still need further testing to confirm a diagnosis of TCC.

BRAF mutation assay. If you want to perform an early diagnostic test, Dr. Johnson recommends this one. You can use it to detect possible TCC up to four months prior to any clinical signs becoming evident. It can also be used for diagnosis and monitoring effectiveness of treatment.

You. Can. Do. This!

At Fetch dvm360 conference, we're the support system you need. With every conference this year, we intend to nurture your mind (meaning quality CE for days) while also encouraging you to take stock of your physical and emotional health. Register now.

What are the treatment options?

A quick note about cats:

They can get TCCs too but it's rare. In cats it seems to be more common in males instead of females, and it's not as frequent in the trigone of the bladder like we see in dogs. Typical survival time is five to eight months due to progressive disease. Remember, you can't use cisplatin in cats due to renal toxicity.

Treatment options for TCCs include:

> Surgery (including permanent cystotomy)

> Radiation therapy

> Metronomic chemotherapy

> Medical management

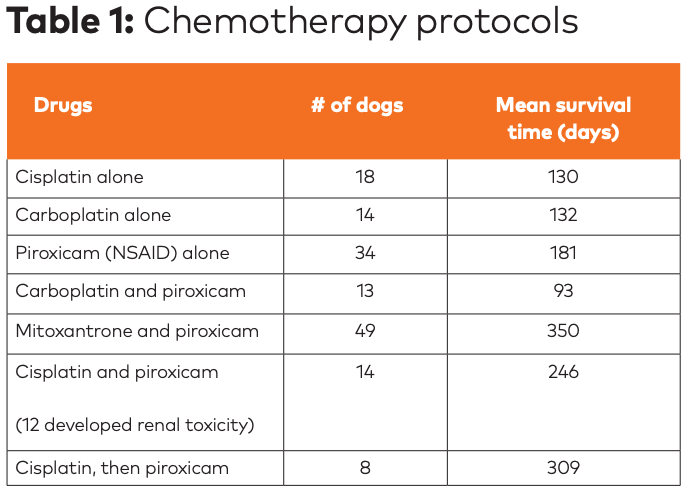

Although surgery is an option, the location that we most commonly find TCCs, the trigone, is a location where surgery is often not an option. In these cases, Dr. Johnson will often try a combination therapy of chemo and NSAIDs.7-16 Here's a look at the efficacy of various chemotherapy protocols:

Dr. Johnson suggests these chemo protocols:

> Mitoxantrone: 5 mg/m2 IV once every three weeks for six treatments.

> Carboplatin: 250 mg/m2 IV once every three weeks for six treatments.

> Vinblastine: 2 mg/ m2 every two weeks for six to eight treatments. Dr. Johnson recommends starting with this if the patient already has kidney disease.

> Prioxicam (NSAID): 0.3 mg/kg once a day for one month, then every other day for six months to help preserve kidneys. Monitor the blood urea nitrogen/creatinine ratio and urine specific gravity during treatment.

Metronomic chemotherapy is just low doses of chemotherapy, administered frequently and is less toxic. Dr. Johnson typically divides her regular doses by 15 and administers chemo at that dose every other day.

Frequent Fetch dvm360 speaker Dr. Hilal Dogan practices medicine in Denver, Colorado. She started the Veterinary Confessionals Project as a senior veterinary student at Massey University in New Zealand.

References

- Mutsaers AJ, Widmer WR, Knapp DW: Canine transitional cell carcinoma, J Vet Intern Med 17:136–144, 2003.

- Knapp DW, Glickman NW, DeNicola DB, et al: Naturally-occurring canine transitional cell carcinoma of the urinary bladder: a relevant model of human invasive bladder cancer, Urol Oncol 5:47–59, 2000.

- Glickman LT, Schofer FS, McKee LJ: Epidemiologic study of insecticide exposures, obesity, and risk of bladder cancer in household dogs, J Toxicol Environ Health 28:407–414, 1989.

- Raghavan M, Knapp DW, Dawson MH, et al: Topical spot-on flea and tick products and the risk of transitional cell carcinoma of the urinary bladder in Scottish terrier dogs, J Am Vet Med Assoc 225:389–394, 2004.

- Glickman LT, Raghavan M, Knapp DW, et al: Herbicide exposure and the risk of transitional cell carcinoma of the urinary bladder in Scottish terrier dogs, J Am Vet Med Assoc 224:1290–1297, 2004.

- Raghavan M, Knapp DW, Bonney PL, et al: Evaluation of the effect of dietary vegetable consumption on reducing risk of transitional cell carcinoma of the urinary bladder in Scottish terriers, J Am VetMed Assoc 227:94–100, 2005.

- Mutsaers AJ, Widmer WR, Knapp DW: Canine transitional cell carcinoma, J Vet Intern Med 17:136–144, 2003.

- Knapp DW: Animal models: naturally occurring canine urinary bladder cancer. In Lerner SP, Schoenberg MP, Sternberg CN, editors: Textbook of bladder cancer, Oxon, United Kingdom, 2006, Taylor and Francis.

- Knapp DW, Richardson RC, Chan TCK, et al: Piroxicam therapy in 34 dogs with transitional cell carcinoma of the urinary bladder, J VetIntern Med 8:273–278, 1994.

- Henry CJ, McCaw DL, Turnquist SE, et al: Clinical evaluation of mitoxantrone and piroxicam in a canine model of human invasive urinary bladder carcinoma, Clin Cancer Res 9:906–911, 2003.

- Arnold EJ, Childress MO, Fourez LM, et al: Clinical trial of vinblastine in dogs with transitional cell carcinoma of the urinary bladder, J Vet Intern Med 25(6):1385–1390, 2011.

- Chun R, Knapp DW, Widmer WR, et al: Cisplatin treatment of transitional cell carcinoma of the urinary bladder in dogs: 18 cases (1983-1993), J Am Vet Med Assoc 209:1588–1591, 1996.

- Moore AS, Cardona A, Shapiro W, et al: Cisplatin (cisdiamminedichloroplatinum) for treatment of transitional cell carcinoma of the urinary bladder or urethra: a retrospective study of 15 dogs, J Vet Intern Med 4:148–152, 1990.

- Greene SN, Lucroy MD, Greenberg CB, et al: Evaluation of cisplatin administered with piroxicam in dogs with transitional cell carcinoma of the urinary bladder, J Am Vet Med Assoc 231:1056–1060, 2007.

- Boria PA, Glickman NW, Schmidt BR, et al: Carboplatin and piroxicam in 31 dogs with transitional cell carcinoma of the urinary bladder, Vet Comp Oncol 3:73–78, 2005.

- Knapp DW, Glickman NW, Widmer WR, et al: Cisplatin versus cisplatin combined with piroxicam in a canine model of human invasive urinary bladder cancer, Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 46:221–226, 2000.