Diagnosing and treating rear limb disorders in dogs (Proceedings)

Hip dysplasia is an abnormal development of the coxofemoral joint.

Hip dysplasia is an abnormal development of the coxofemoral joint. The syndrome is characterized by subluxation or complete luxation of the femoral head in the younger patient while in the older patient mild to severe degenerative joint disease is present. Laxity in the hip joint is responsible for the early clinical signs and joint changes. Subluxation stretches the fibrous joint capsule, producing pain and lameness. When the surface area of articulation is decreased, this concentrates the stress of weight bearing over a small area through the hip joint. Subsequently, fractures of the trabecular cancellous bone of the acetabulum can occur, causing pain and lameness. The cancellous bone of the acetabulum is easily deformed by the continual dorsal subluxation of the femoral head. This piston-like action causes a wearing of the acetabular articular surface from a horizontal plane to a more vertical plane causing subluxation to worsen. The physiologic response to joint laxity is proliferative fibroplasia of the joint capsule and increased thickness of the trabecular bone. This relieves the pain associated with capsular sprain and trabecular fractures. However, the surface area of articulation is still decreased causing premature wear of articular cartilage, exposure of subchondral pain fibers and lameness. This may occur early in the pathologic process or later in life. There are two general recognizable clinical syndromes associated with hip dysplasia: (1) patients 5 to 16 months of age, (2) patients with chronic degenerative joint disease. Patients in group 1 present with lameness between 5 to 8 months of age. Symptoms include difficulty when rising after periods of rest, exercise intolerance, restlessness at night, and intermittent or continual lameness. The majority of young patients will spontaneously improve clinically around 15 to 18 months of age. This clinical improvement is due to pain relief as proliferative fibrous tissue prevents further capsular sprain, and increased thickness of the subchondral bone prevents trabecular fractures. If symptoms occur later in life, they may include difficulty in rising, exercise intolerance, lameness following exercise, atrophy of the pelvic muscle mass, and a waddling gait with the rear quarters. Physical findings in the younger group of patients include pain during external rotation and abduction of the hip joint, poorly developed pelvic muscle mass, and exercise intolerance. Hip exam performed under general anesthesia will reveal abnormal angles of reduction and subluxation reflecting excessive joint laxity. Physical findings in the older group of patients include pain during extension of the hip joint, reduced range of motion, atrophy of the pelvic musculature, and exercise intolerance. Radio graphically, there are seven grades of variation in the congruity between the femoral head and acetabulum established by the Orthopedic Foundation for Animals. Excellent, good, fair, and near normal are considered within a range of normal. Dysplastic animals fall into the categories of mild, moderate, and severe. It is important to note that clinical signs do not always correlate with radiographic findings. Recently, patients have been evaluated using a distraction index where the degree of hyperlaxity is measured and correlated with standards for each breed.

Treatment is dependent upon the age of the patient, the degree of patient discomfort, physical and radiographic findings, client expectations of patient performance, and financial capability of the client. Conservative treatment is beneficial to a large number of patients in both the young and older patient groups. Conservative management is divided into acute management and long term management. When a dog exhibiting signs of hip dysplasia enters the clinic, it is generally because they have sprained the hip joint. The dysplastic joint is either hyperlax (young dog) has a limited range of motion (mature dog). In either case, the joint is easily sprained and the dog that is presented with symptoms has generally overused (sprained) the hip joint. The management of the case at this time period is the same as treating any other acute sprain. Rest, physical therapy, and non-steroidal analgesics will relieve signs in the majority of patients. Rest is just that!!!, controlled activity with slow walking on a leash only. There should be NO free activity for 2 weeks. Physical therapy includes cold therapy for the initial 1-4 days. Commercial cold packs are the most convenient and precise way to apply cold therapy. The application of cold should only be 5-10 minutes. The attending veterinarian must emphasize that REST and PT are the most important considerations when treating an acute sprains.

Following the acute phase of treatment, the attending veterinarian must consult with the owner regarding longterm management of the dysplastic dog. The foundation for long term management of any arthritic joint is weight control, exercise therapy, and anti-inflammatory drugs or supplements. The majority of mature dogs with hip discomfort are over weight. Studies have shown a significant improvement in function if an ideal target weight is achieved. The foundation for weight control is exercise therapy, diet, and owner behavior modification. Administration of drugs (NSAIDs, steroids, PSGAGs, Hyaluronate) or supplements (glucosamine, chondroitin sulfate, manganese) are useful to control discomfort. This is particularly true in the early stages of treatment before the benefits of weight reduction and exercise therapy are realized. The administration of drugs should be at a minimum level (dose and frequency) to achieve comfort. Supplements of glucosamine, chondroitin sulfate and manganese alone or in combination have been shown in vitro as well as in clinical studies to ameliorate discomfort or reduce the dose of drugs needed to control discomfort.

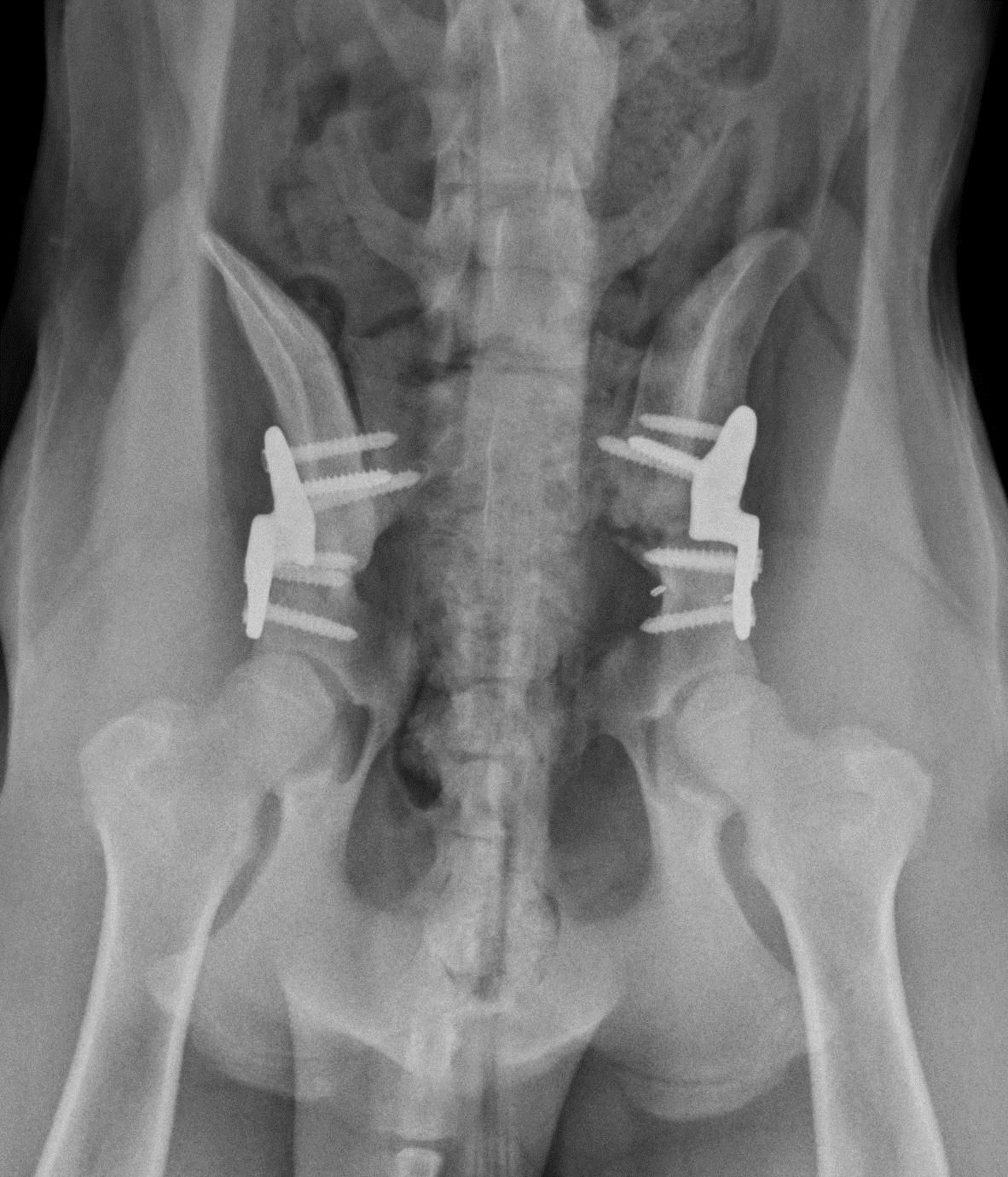

Surgical intervention also is divided into techniques useful in the younger population and those useful in mature dogs. Techniques useful in the younger population include Triple Pelvic Osteotomy (TPO), Double Pelvic Osteotomy, femoral head ostectomy, and possibly total hip replacement. My preference in this aged dog is either a TPO or DPO. The advantage of DPO is that the floor of the pelvic canal is stable is that the ischium does not undergo an osteotomy as in a TPO. This concept allows for greater patient comfort and therefore, the ability to perform a bilateral DPO at the same setting. This reduces postoperative rehabilitation time and allows more rapid return to function. Pelvic osteotomy is used in the group of younger patients to axially rotate and lateralize the acetabulum in an effort to increase dorsal coverage of the femoral head. This procedure is indicated in patients that will lead athletic lives such as the working breeds or in those patients in which the client wishes to arrest or slow the progress of osteoarthritis associated with hip dysplasia. The most favorable prognosis is in patients having minimal existing radiographic degenerative changes and an angle of reduction less than 45 degrees and angle of subluxation less than 15 degrees. The prognosis is less favorable in patients with existing degenerative changes and angles of reduction and subluxation greater than those given above. The details of the technique are beyond the scope of this handout. Briefly, the degree of axial rotation of the acetabulum is set by the previously determined angles of reduction and subluxation. The angle of reduction is the maximum degree of rotation and the angle of subluxation is the minimum degree of rotation. The most commonly used angle of acetabular axial rotation is slightly less than the measured angle of reduction. The pelvis is cut through the pubic brim and body of the ilium. The acetabulum is rotated axially, lateralized and stabilized with the appropriate osteotomy plate. The use of locking technology is an advantage that has decreased post operative implant failure. Postoperatively the patient is restricted to exercise on a leash only until radiographic healing of the osteotomies is complete

.Pre Op

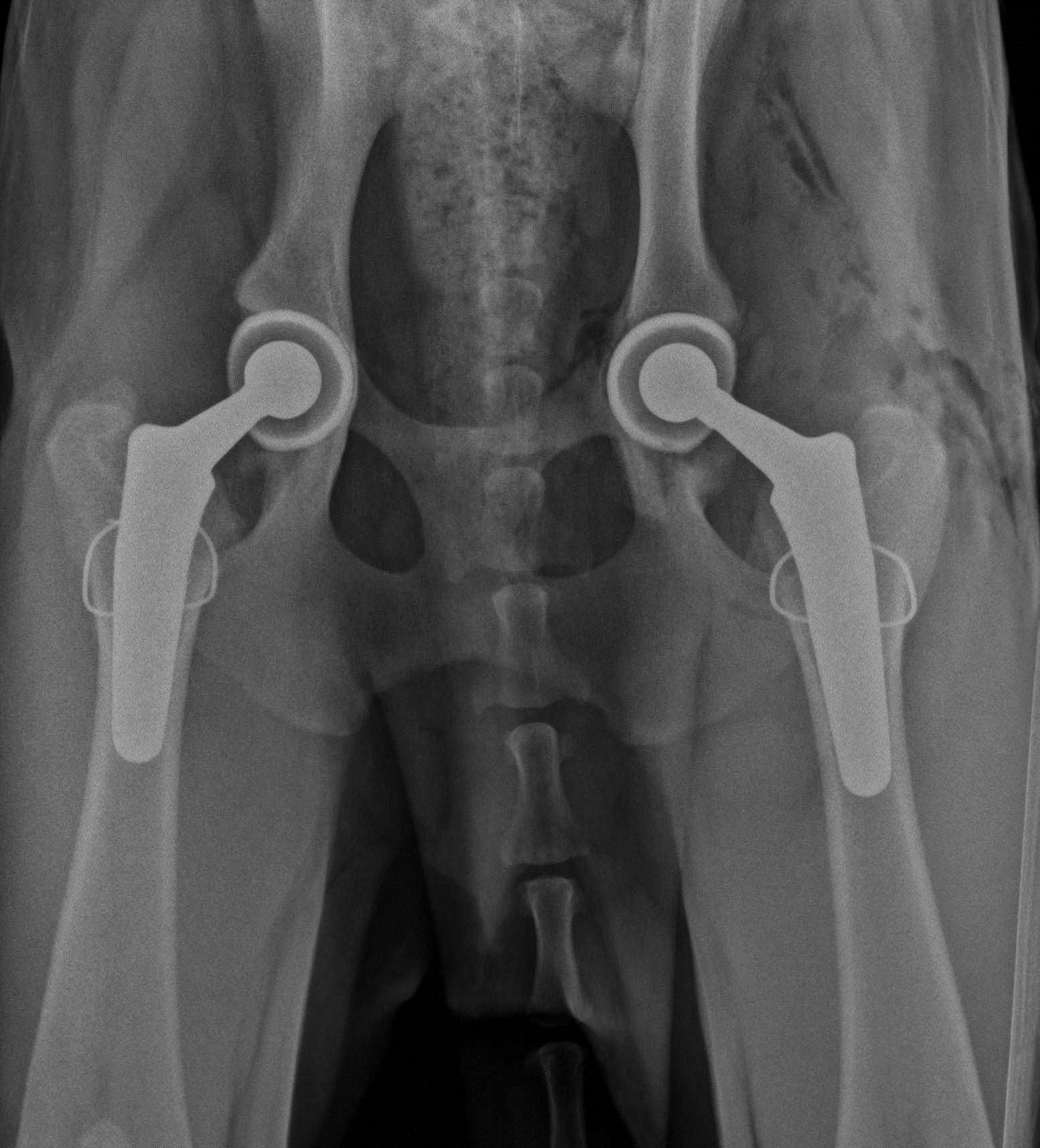

Post Op

6 Weeks

In the older dogs, my preference is total hip replacement or conservative management. Femoral head ostectomy is an option in cases where conservative management is no longer effective and financial constraints precludes Total Hip Replacement. Advancement in Total Hip Replacement is the advent of cementless systems. Cementless systems have decreased the incidence of acetabular cup loosening and femoral stem loosening. Hybrid insertion with cementless cup and cemented stem are often used in dogs with “stove pipe”, ie, uniform diameter marrow cavity.

Diagnosis of the CCL deficient stifle

Examination

Perform the initial examination of the stifle with the animal standing. Simultaneously palpate both stifles to detect swelling. A swollen stifle usually indicates degenerative joint disease. The patellar ligament becomes less distinct with joint effusion and the medial aspect of the stifle enlarges because of capsular thickening and osteophyte formation. Palpate the stability of the patella with the hip joint in full extension. Ask the animal to sit; observe the flexion of the stifle and tarsus. The earliest sign of stifle joint pathology is failure to dorsiflex the tarsus fully (compare to the opposite normal side).

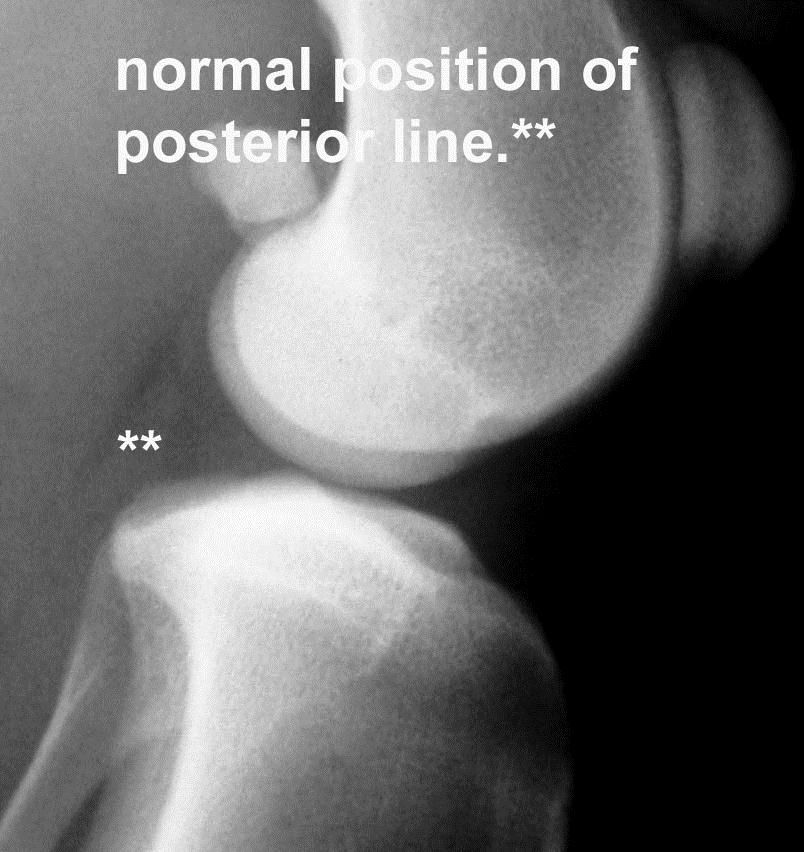

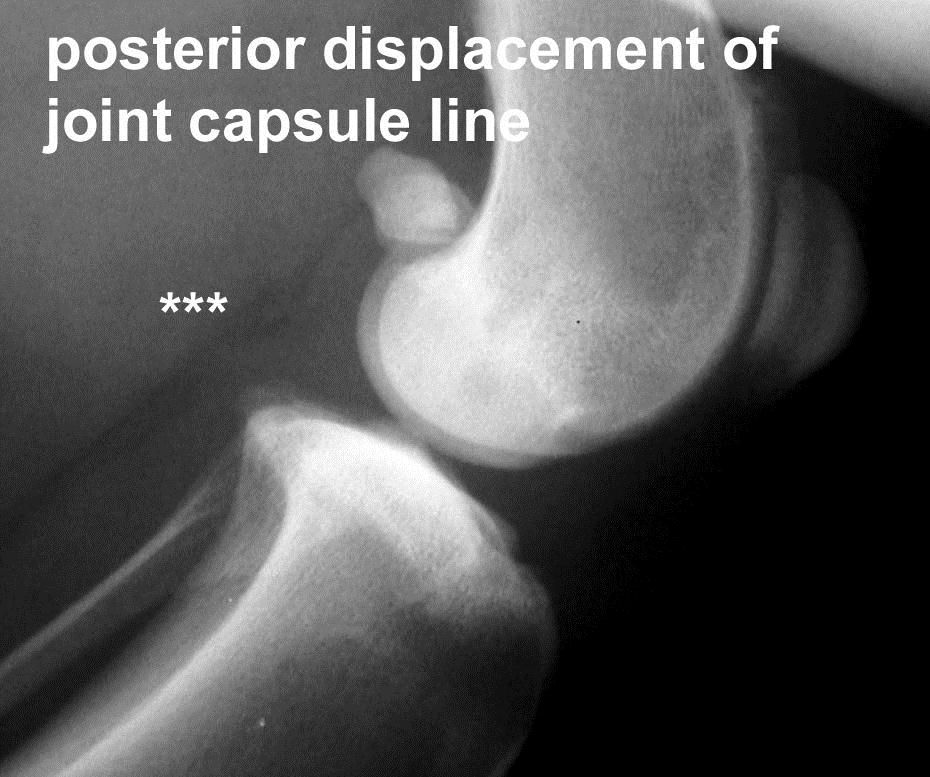

Imaging

Early diagnosis is dependent upon radiographic presence of joint effusion. A radiolucent line adjacent to the caudal joint capsule is representative of fatty tissue in the space between the joint capsule and popliteal muscle. Caudal displacement of this line is representative of joint effusion. This is one of the earliest radiographic indications of partial anterior cruciate ligament injury. As changes progress, typical radiographic signs of DJD will be noted.

Stabilization of the CCL deficient joint can be accomplished through a variety of methods. Surgical techniques have been developed including placement of intra-articular grafts, insertion of suture material and/or advancement of periarticular structures outside the joint (extracapsular), and tibial osteotomies that alter joint mechanics. The technique of choice is based on surgeon experience. Tibial plateau leveling techniques are preferred by the author in large athletic breeds, with early partial CCL injury, and in dogs/cats with excessive slope. Recent double blind study showed that in larger breeds of dogs, the Nylon crimp technique was not as effective in all outcome parameters as a leveling osteotomy. A number of reasons why the nylon / crimp technique is ineffective have been elucidated. The placement of the nylon (attachment sites at the femur/tibia) are very non-isometric and predispose to suture elongation/breakage. The nylon material itself undergoes stress relaxation/creep, ie, elongates under continual load. Newer materials (Arthrex FiberWire/Tape) have improved structural/mechanical properties.

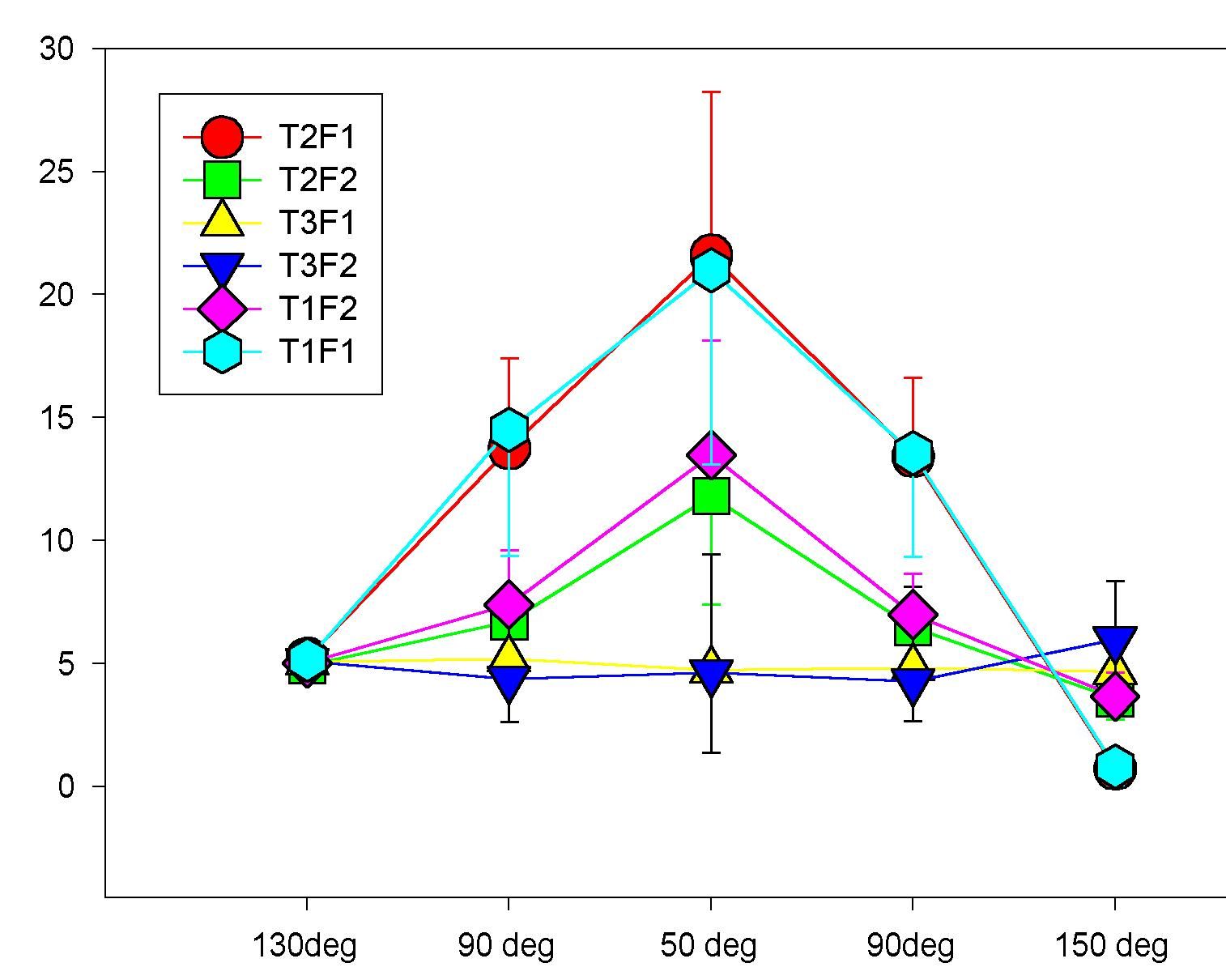

More isometric sites have been identified; note the ligament is very complex and there is no true one isometric site. Studies in our lab at TAMU have identified near isometric sites.

A discussion of the site(s) location and technique of application are presented below. Additionally, a leveling osteotomy technique is described for those who wish to apply this method based upon personal preference/indications.

Recommended sites for isometric suture placement

Locating the F2 site

The F2 site is located at the level of the distal pole of the fabella. Placement of the anchor is critical. The anchor must be placed in the femoral condyle as far distal and as far caudal as is possible. An anchor placed to far proximal or anterior is at risk for pull out or suture failure. To locate the correct placement site in the femoral condyle, palpate the distal pole of the fabella. Make a vertical incision through the capsular tissue to expose the joint line between the fabella and caudal margin of the femur. Locate the proper position for the anchor just distal to the fabella-femoral jont line and as far caudal as possible. A hole is pre-drilled with a 2mm drill bit (or 1/16 Steinmann pin) at the correct anchor position. The drill hole is angled directed toward the patella to cranial to eliminate the risk of entering the joint. Insert the appropriate size anchor.

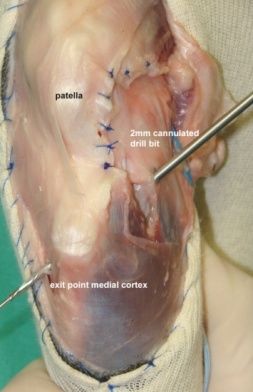

Locate the T3 site at the proximal tibia

First locate the protuberances cranial and caudal to the long digital extensor groove. Make a vertical incision through the capsular tissue overlying the extensor groove. Palpate and locate the protuberance just caudal to the extensor groove; this is the site for placement of the first drill hole. At this site beginning as proximal as is possible without entering the joint, insert a .045 k-wire. The K-wire is directed to glide beneath the extensor groove to exit through the medial cortex of the proximal tibia. With the K-wire in place, place a 2mm cannulated drill bit over the wire to create the first drill hole. Drill over the K-wire to exit through the medial cortex. Leave the drill bit in place and remove the K-wire. Through the cannulated hole in the drill bit, place a nytinol Arthrex suture passer such that the loop is lateral. Remove the drill bit and leave the suture passer in the drill hole.

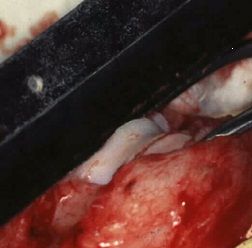

Passing the suture through the drill hole

Place one of the suture ends through the loop in the nytinol suture passer. Only place about 1cm of the suture through the loop to decrease suture drag as it passes though the drill hole. Pull the suture passer medial such that the free end of the suture exits through the medial cortex. Place the free end of the suture through a two hole button such that the button will lie against the medial cortex when the suture is pulled taught. Re-insert the nytinol suture passer through the drill hole such that the loop is positioned medial. Place the free end of the suture through the nytinol loop (1cm of suture end) and pull the suture laterally. Now both free ends of the suture are lateral and ready to be tied.

Tying the suture

Place the limb in normal standing position (140 degrees). Place the initial double throw of a surgeons knot and check cranial drawer. Do not over constrain; there should be 2-3mm cranial translation. When satisfied with stability, complete the surgeons knot and place 4 additional half throws. Check range of motion and cranial drawer.

Knotless swivelock

The 5.5mm PEEK SwiveLock is recommended for dogs weighing 50lbs or greater. One strand of 2mm Fibertape (2 limbs) is inserted for dogs up to 70 lbs or so; two strands (4 limbs) of 2mm fiberTape is recommended for dogs greater than 70 lbs. The F2 and T3 sites described previously are used in this application.

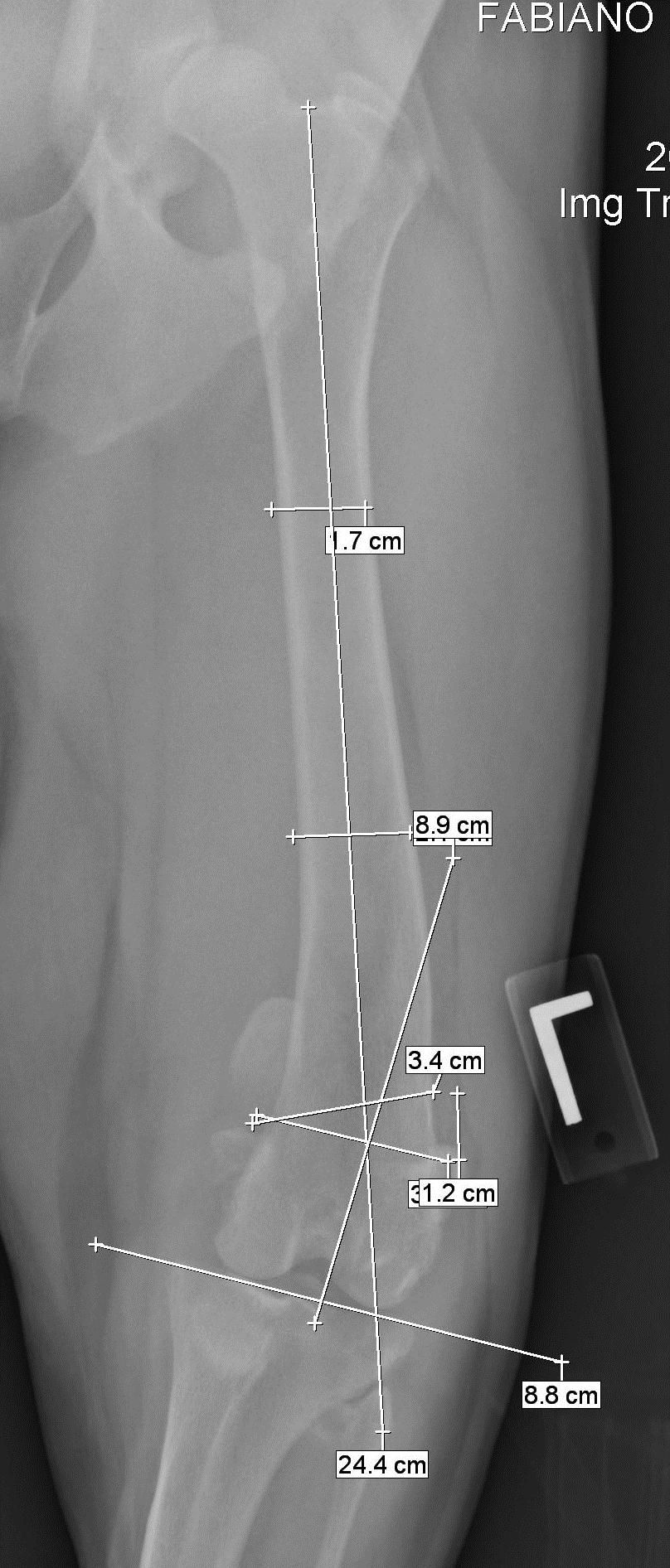

Concept of CORA based leveling osteotomy

Recent studies have shown joint mechanical alteration that may be contributory to articular cartilage lesions noted on 2nd look arthroscopy. One explanation for reported abnormal joint mechanics with Tibial Plateau Leveling Osteotomy is that the standard Slocum osteotomy is not based on the anatomic CORA. As such, the Axis of Correction (ACA) is not aligned with the anatomic CORA resulting in mal-alignment of the proximal and distal anatomic axis and secondary translation. The result is caudal displacement of the weight bearing axis and a focal increase in joint force. When rotated to the recommended 5 degrees, the long-term effect is loss of compliance of cranial supporting structures such as the fat pad and joint capsule. Encroachment of the cranial supporting structures (joint capsule) on the cranial articular surface of the medial/lateral femoral condyles can result in abrasion of the articular cartilage.

Surgical techniques for stabilization of the patella

Deepening of the trochlear groove

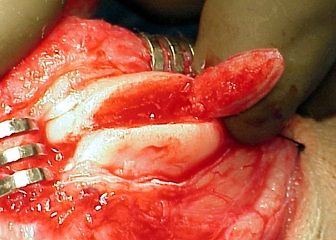

If the medial and lateral trochlear ridges do not constrain the patella, the trochlear groove must be deepened. This technique is generally necessary in dogs/cats with a grade III or IV luxation. Deepening the groove may be achieved with a trochlear wedge recession, trochlear block recession, or trochlear resection.

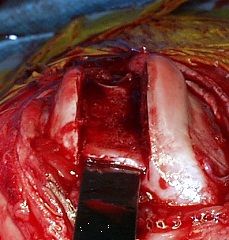

Trochlear wedge recession deepens the trochlear groove to restrain the patella and maintains the integrity of the patellofemoral articulation. Make a diamond shaped outline cut into the articular cartilage of the trochlea with a scalpel (use smooth arcs rather than corners on the lateral and medial sides of the diamond). The width of the cut must be sufficient at its' midpoint to accommodate the width of the patella. An osteochondral wedge of bone and cartilage is removed by following the outline previously made. Make the osteotomy so that the two oblique planes that form the free wedge intersect distally at the intercondylar notch and proximally at the dorsal edge of the trochlear articular cartilage. Use caution to avoid making the wedge too long (may affect cruciate ligament insertions) or too deep (may go through the caudal aspect of the femur).

Trochlear block recession

Is performed similarly to the wedge recession. Some surgeons find the block recession most appropriate for dogs that seem to luxate primarily with the stifle joint in extension, and for larger breed dogs. The advantage of the block recession is deeper placement of the patella and more advantageous proximal tracking of the patella into the trochlear groove.

Tibial tuberosity transposition

Tibial tuberosity or crest transposition is an effective method of treatment for grades II, III, and IV patellar luxations.

Medial release: The medial joint capsule is thicker than normal and contracted in patients with grade III or Grade IV patella luxations. In this group of animals, the medial joint capsule and retinaculum must be released to allow lateral placement of the patella. The pull of the sartorius muscles and vastus medialis muscle directs the patella medially, the insertions of these muscles at the proximal patella are released. Redirect the insertions and suture them to the vastus intermedius.

Lateral reinforcement

Reinforcement of the lateral retinaculum is accomplished with suture placement and imbrication of the fibrous joint capsule, by placement of a fascia lata graft from the fabella to the parapatellar fibrocartilage, patella sling suture, or excision of redundant retinaculum.

Femoral varus/valgus correction is required in cases where the angulation of the distal femur precludes correct alignment of the extensor mechanism. This abnormal / excessive varus/valgus is present with cases of Grade 4 patella luxation. The method of planning correction is based upon the CORA methodology. CT imaging and reconstruction are the most accurate method of determining correction. In severe cases, prototype development is ideal. Many centers do not have the ability to perform CT/reconstruction and prototype development; accurate radiographic positioning and planning will suffice except in the more severe cases. These cases can be very complex and therefore recommended only for the experienced surgeon.