New strategies for successful feline parasite control

Cats are host to a variety of internal and external parasites. Despite the documented prevalence and zoonotic importance of these parasites, many pet owners and some veterinarians aren't convinced that comprehensive feline parasite control strategies are needed. This viewpoint may stem from the previous lack of safe, effective, and convenient broad-spectrum parasiticides and the difficulties in acquiring adequate fecal samples. Fortunately, newer broad-spectrum agents (Table 1), particularly those with label claims against heartworms and fleas, allow veterinarians to eliminate a higher percentage of feline parasites. Let's review some of the key feline parasites and discuss new strategies for controlling them.

Cats are host to a variety of internal and external parasites. Despite the documented prevalence and zoonotic importance of these parasites, many pet owners and some veterinarians aren't convinced that comprehensive feline parasite control strategies are needed. This viewpoint may stem from the previous lack of safe, effective, and convenient broad-spectrum parasiticides and the difficulties in acquiring adequate fecal samples. Fortunately, newer broad-spectrum agents (Table 1), particularly those with label claims against heartworms and fleas, allow veterinarians to eliminate a higher percentage of feline parasites. Let's review some of the key feline parasites and discuss new strategies for controlling them.

Dr. Byron L. Blagburn

Parasites

Although cats are host to numerous internal parasites, heartworms, roundworms, and hookworms are the most important. Fortunately, all three are easily preventable with available medications (

Table

1

).

Heartworms. Serologic studies indicate that cats' exposure to heartworm-infected mosquitoes is common in many regions of the United States. Although most infected cats are asymptomatic, it's impossible to predict when and under what conditions asymptomatic cats will develop clinical heartworm disease. Symptomatic cats present with vague signs such as mild dyspnea, intermittent coughing, and occasional vomiting that's not associated with eating. Respiratory signs are similar to those observed with feline asthma. A small percentage of cats present with peracute dirofilariasis or die suddenly. This peracute presentation also mimics signs of feline asthma or cardiomyopathy (dyspnea). Many of these cats are clinically normal before the acute heartworm-induced event. Some affected cats also lose weight or develop diarrhea without respiratory signs.

Table 1 Selected Feline Internal and External Parasiticides

Problems associated with diagnosing and treating feline heartworm disease emphasize the need to prevent infection, especially in high prevalence areas. Essentially, feline heartworm disease isn't treatable because there isn't a safe, effective adulticide for cats. You can treat and alleviate clinical signs, but you can't eliminate heartworms safely. To make matters worse, very few infected cats test positive using either antigen or microfilaria detection methods. Many infected cats harbor fewer than three worms (Figure1).

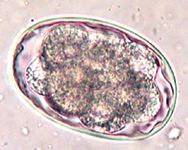

Roundworms. Although surveys indicate that roundworms (Figure2) are the most common internal parasite in cats, the importance of Toxocaracati infections is often underestimated. Contrary to the beliefs of many veterinarians and pet owners, these surveys also indicate that cats may harbor roundworms throughout their lives, resulting in substantial environmental contamination (Figure3). The high prevalence of roundworms in cats stems from the multiple ways infection can occur (e.g., embryonated eggs; transmammary transmission; paratenic hosts, such as rats and mice; and the long life of embryonated eggs in the environment). One T. cati female can produce thousands of eggs per day, and eggs can live several years in protected indoor and outdoor environments.

Figure 1 Most feline heartworm infections consist of only a few worms. Often a single worm is present, as this case illustrates.

Clinical signs of feline roundworm infections may include an enlarged abdomen, a failure to thrive, vomiting, and diarrhea. Low T. cati worm burdens can result in low egg numbers in feces, so an accurate diagnosis requires that fecal flotation procedures be performed properly. Furthermore, T. cati infections are not restricted to kittens. In a survey I conducted, 23 out of 27 cats infected with T. cati were 2 years old or older; 10 out of 27 were 3 years old or older.

Figure 2 Anterior end of Toxocara cati (roundworm). The broad, arrowhead-shaped cervical alae help differentiate this parasite from other canine and feline roundworms.

Toxocara cati is also a confirmed zoonotic agent and may cause diseases (larva migrans) in people who accidentally ingest embryonated eggs from the environment. Visceral larva migrans results from larval migration and damage to internal organs, such as the liver, lungs, kidneys, or brain. Ocular larva migrans occurs when larvae migrate to the posterior chamber of the eye, which can lead to granulomatous retinitis, retinal detachment, loss of vision, or, in severe cases, blindness. Recent research indicates that ocular damage caused by T. cati may be as severe as the damage caused by Toxocara canis. In addition, 24 reports document that adult T. cati infections occur more frequently in people than adult T. canis infections.

Hookworms. The prevalence of hookworm (Ancylostoma tubaeforme) infections in cats is exceeded only by roundworms (Figure4). Cats acquire A. tubaeforme infections by ingesting infective larvae, through skin penetration, and from paratenic hosts, such as rats and mice. Apparently, neither transplacental nor transmammary transmission of hookworms occurs in cats.

Figure 3 Nonembryonated egg of Toxocara cati (roundworm). This egg is similar to Toxocara canis but smaller.

Experimental study results suggest that hookworm infections in cats can cause weight loss and anemia. Interestingly, another scientific study shows that a mean infection level of 100 worms was all that was needed to cause death in infected kittens.

Like roundworms, hookworm infections can occur in older cats, too. In another survey I conducted, 22 out of 27 cats infected with A. tubaeforme were 2 years old or older; 13 out of 27 were 3 years old or older.

Ectoparasites. Of all the ectoparasites that can infest cats in the United States, fleas (Ctenocephalidesfelis) and ear mites (Otodectescynotis) are the most common. The less common feline ectoparasites include lice (Felicolasubrostratus), face mange mites (Notoedrescati), walking dandruff mites (Cheyletiellablakei), and fur mites (Lynxacarusradovskyi) (Table2).

Fleas are a major cause of dermal irritation and allergy and vectors of such disease agents as Bartonellahenselae (cat scratch disease). Studies also indicate that fleas may carry the infectious agents Rickettsiafelis and Haemoplasma species. The flea's role in actual transmission of these agents is not yet clear. Ear mites are frequent causes or contributors to otitis involving the external ear canal (Figure5).

Figure 4 Nonembryonated egg of Ancylostoma tubaeforme (hookworm).

Both fleas and ear mites can be controlled with many of the approved agents listed in Table1. Interestingly, a number of published studies indicate that certain ectoparasiticides are also effective in eliminating N. cati, C. blakei, and F. subrostratus, although these products do not carry label claims against them.

Figure 5 Adult female ear mite (Otodectes cynotis). This parasite commonly causes inflammation in cats' external ears.

Control strategies

Before deciding on treatment and selecting a product, it's important to discuss prevention strategies with clients, such as those presented in

Table

3

. It's equally important to perform the most sensitive tests available for an accurate diagnosis, especially when conducting fecal examinations. Be sure to obtain adequate sample sizes and use centrifugal flotation diagnostic procedures. An adequate fecal sample size is 1 gram (a cube about 1/2 in on a side).

For recommendations on heartworm testing in at-risk cats, consult the 2005 Companion Animal Parasite Council (CAPC) guidelines (www.capcvet.org). The difficulty of diagnosing feline heartworm infections and the unpredictable disease episodes associated with them make these guidelines particularly helpful.

Table 2 Less Common Ectoparasites of Cats

When selecting a product for successful feline parasite control, consider the following:

- the biology and behavior of feline parasites

- primary parasitic disease control in cats

- zoonotic disease prevention in people

- maximum owner compliance

- the spectrum of parasites controlled

- the effective monitoring of parasiticide usage

And remember: Controlling common internal parasites, such as roundworms and hookworms, should begin in kittens. The highest contamination rates with parasite eggs occur during the first year of a cat's life. Kittens begin shedding roundworm eggs at about 8 weeks of age; hookworm eggs appear in feces within 3 to 4 weeks of age.

An effective control strategy for kittens and young cats, and one that complies with published guidelines, is to treat kittens with effective anthelmintics, such as pyrantel pamoate, beginning at 3 weeks of age and continuing every two weeks until kittens are 8 to 9 weeks old. Treatment initiated at three weeks will eliminate roundworms and hookworms that may be present but aren't producing substantial numbers of eggs.

At 8 to 9 weeks of age, kittens can be placed on effective, broad-spectrum, monthly products that also prevent heartworm infection (Revolution, HeartGard for Cats, Interceptor) or heartworms, fleas, and Otodectescynotis (Revolution). Note that Interceptor and Revolution are effective against T. cati and A. tubaeforme; HeartGard for Cats is effective against A. tubaeforme and A. braziliense (Table 1).

You should also treat queens with broad-spectrum, monthly products throughout pregnancy. This will help prevent environmental contamination and reduce egg numbers. A queen's exposure to eggs can lead to parasite accumulation in her tissues, which may later infect her offspring.

Feline Parasite And Zoonosis Prevention Strategies

If pet owners want to forego treatment because their kittens or cats remain indoors, remind them that queens can carry parasites like T. cati, insects and small rodents can carry parasite eggs or larvae indoors, and fleas can develop in some indoor locations. Plus, veterinarians know that many "indoor" pets are allowed brief periods of time outdoors, where they're exposed to eggs, larvae, fleas, and heartworm-infected mosquitos.

The CAPC guidelines recommend administering year-round heartworm prevention products with additional broad-spectrum activity against roundworms, hookworms, and other parasites as early as possible and throughout a pet's life. Several of the products in Table1 are compatible with this recommendation and can be administered during the first veterinary visit or earlier. Revolution, Interceptor Flavor Tabs, and HeartGard for Cats have label claims against heartworms, fleas, or both. Additional claims against T. cati, A. tubaeforme, Ancylostomabraziliense, or a combination of these parasites are also beneficial. Revolution comes in a topical formulation, providing added convenience for pet owners.

Other published guidelines for controlling feline parasites and other zoonotic agents include the Guidelines for Veterinarians: Prevention of Zoonotic Transmission of Ascarids and Hookworms of Dogs and Cats, from the CDC's division of parasitic diseases (www.cdc.gov/ncidod/dpd/parasites/ascaris/prevention.htm) and the Feline Zoonoses Guidelines from theAmericanAssociationofFelinePractitioners (www.aafponline.org/about_guidlines.htm). Both contain recommendations similar to the CAPC guidelines.

If you haven't already, take the initiative and implement comprehensive parasite control strategies in your practice today. By combining proper diagnostic techniques with the appropriate, broad-spectrum control products, you'll prevent parasites from jeopardizing the health of your feline patients and their owners.

Suggested reading

Blagburn BL. A review of common internal parasites in cats. The Veterinary CE Advisor: An update on feline parasites. Vet Med 2000;95:3-11.

Blagburn BL. Problems associated with intestinal parasites in cats. DVM Newsmagazine 2002;suppl May DVM Best Practices:12-17.

Bowman DD, Hendrix CM, Lindsay DS, et al. Feline clinical parasitology. Ames, Iowa: Blackwell Publishing, 2002.

Akao N, Takayanagi TH, Suzuki R, et al. Ocular larva migrans caused by Toxocara cati in Mongolian gerbils and a comparison of ophthalmologic findings with those produced by T. canis.J Parasitol 2000;86:1133-1135.

Eberhard ML, Alfano E. Adult Toxocara cati infections in U.S. children: Report of four cases. Am J Trop Med Hyg 1998;59:404-406.

Carleton R, Tolbert MK, et al. Prevalence of Dirofilaria immitis and gastrointestinal helminths in cats euthanized at animal control agencies in northwest Georgia. Vet Parasitol 2004;119:319-326.

Nolan TJ, Smith G. Time series analysis of the prevalence of endoparasitic infections in cats and dogs presented to a veterinary teaching hospital. Vet Parasitol 1995;59(2):87-96.

Fisher M. Toxocara cati: An underestimated zoonotic agent. Trends Parasitol 2003;19:167-170.

Dr. Byron L. Blagburn is professor of parasitology in the Department of Pathobiology at Auburn University's College of Veterinary Medicine. He received his master of science degree in parasitology from Andrews University and his doctor of philosophy degree in parasitology from the University of Illinois. Dr. Blagburn received the Beecham Award for Research Excellence in 1987.